The Colorado River Crisis is Here

States fail to reach a deal; Lake Powell Deadpool appears imminent

Valentines Day wasn’t so lovey-dovey on the Colorado River.

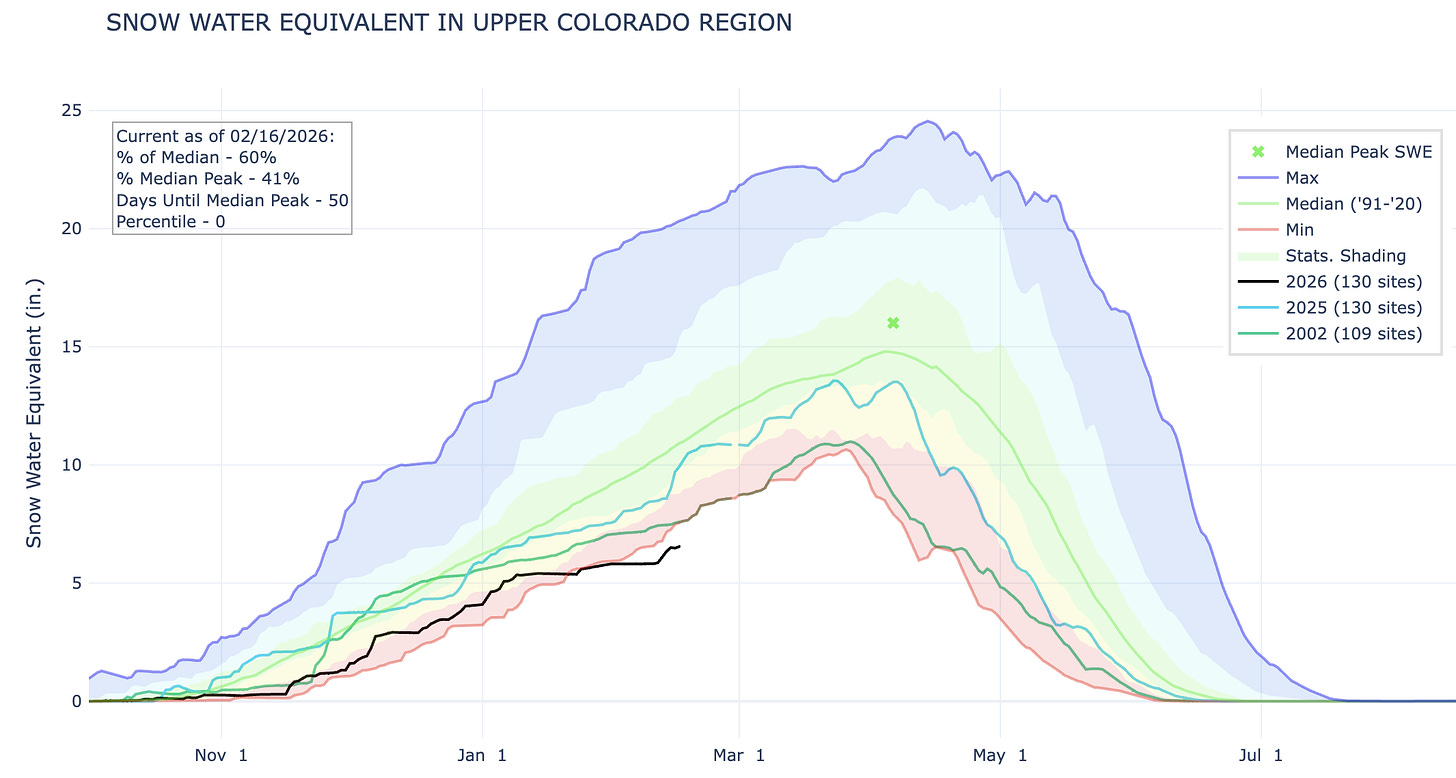

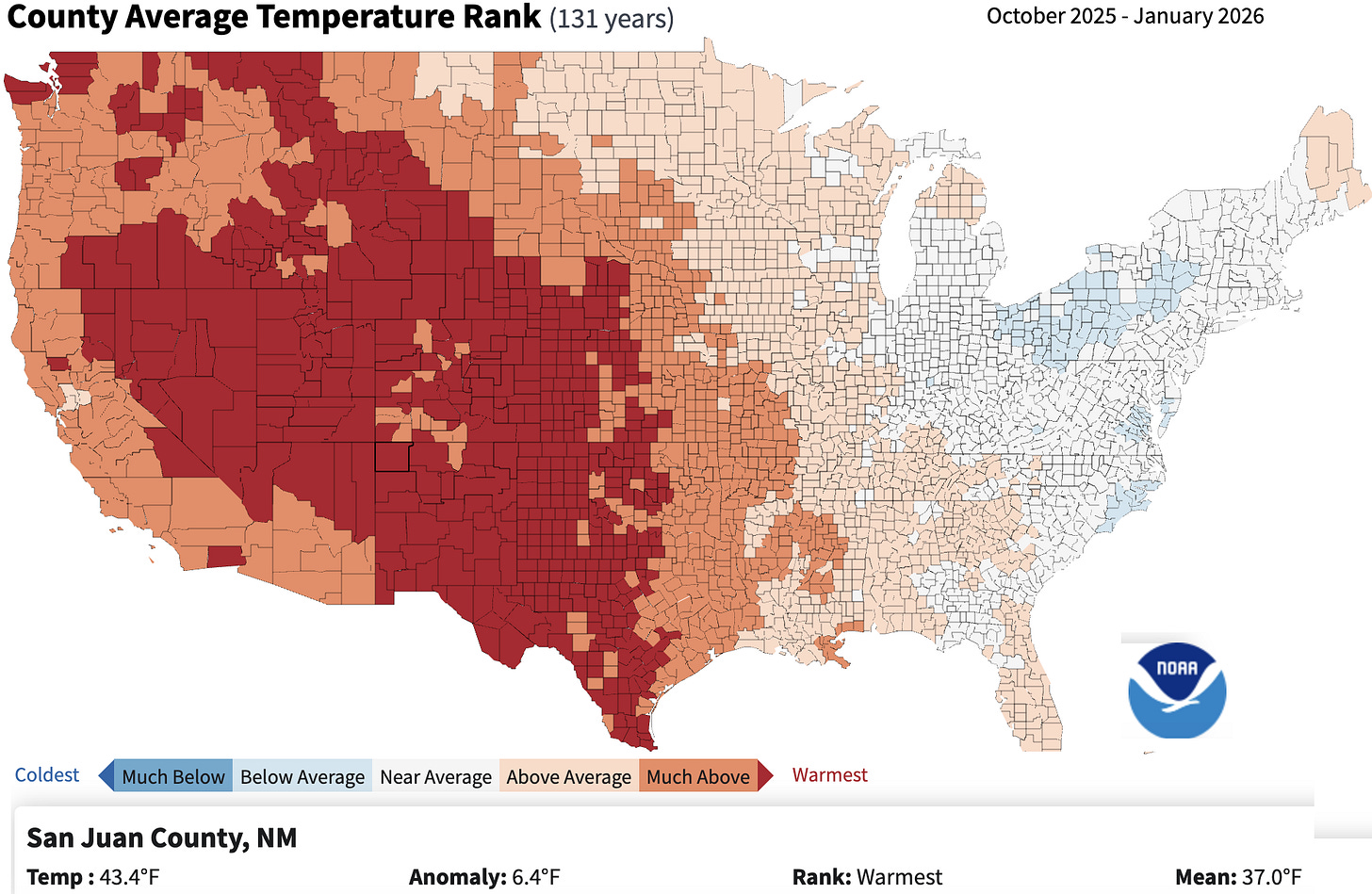

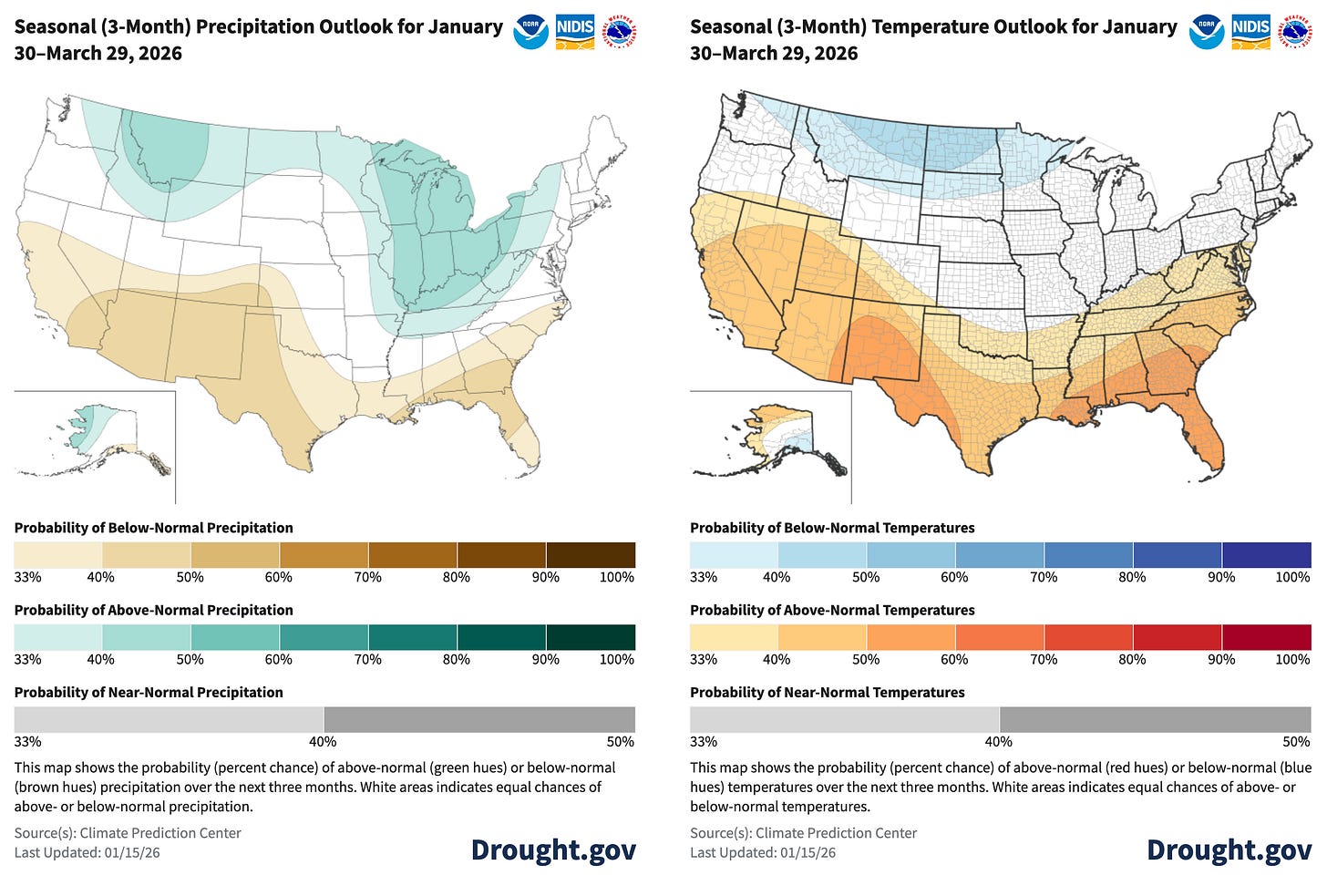

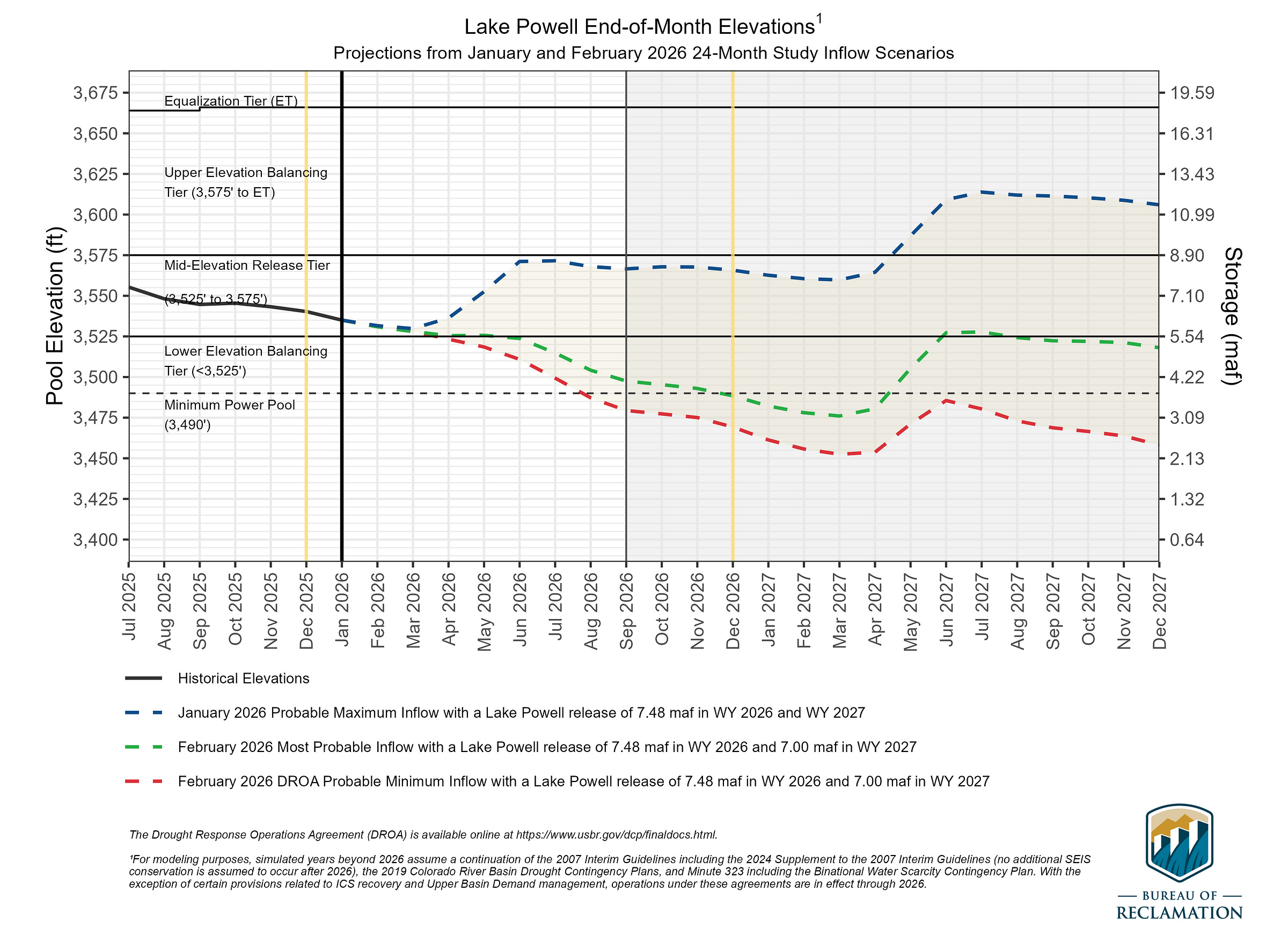

First, the Bureau of Reclamation (BoR) released a grimmer-than-ever spring runoff forecast for the Colorado River and its two big reservoirs. Then the seven Colorado River Basin states announced that they once again had failed to reach an agreement on a plan to bring demand into line with diminishing supplies by the Feb. 14 deadline. While the states have blown by other deadlines since negotiations began in 2022, this time was different in that it triggered the federal government to move forward to impose a post-2026 management plan of its own.

On paper, the states still have until the end of the water year, or Oct. 1, to come up with a deal or to implement an alternate plan. But that may be too little too late to keep Lake Powell’s surface level from dropping below minimum power pool — otherwise known as de facto dead pool — later this year. While the negotiations are over the Colorado River, or rather the water in the river, in many ways they pivot around the need to keep Lake Powell’s surface level above 3,500 feet in elevation. That can only be done by releasing less water out of Glen Canyon Dam, or increasing flows into the reservoir, or a bit of both.

The sticking point in the negotiations hinges upon whether the Upper Basin states will take mandatory and verifiable cuts in water use. The Lower Basin states have already taken cuts, and have agreed to take more, but only if the Upper Basin does the same.

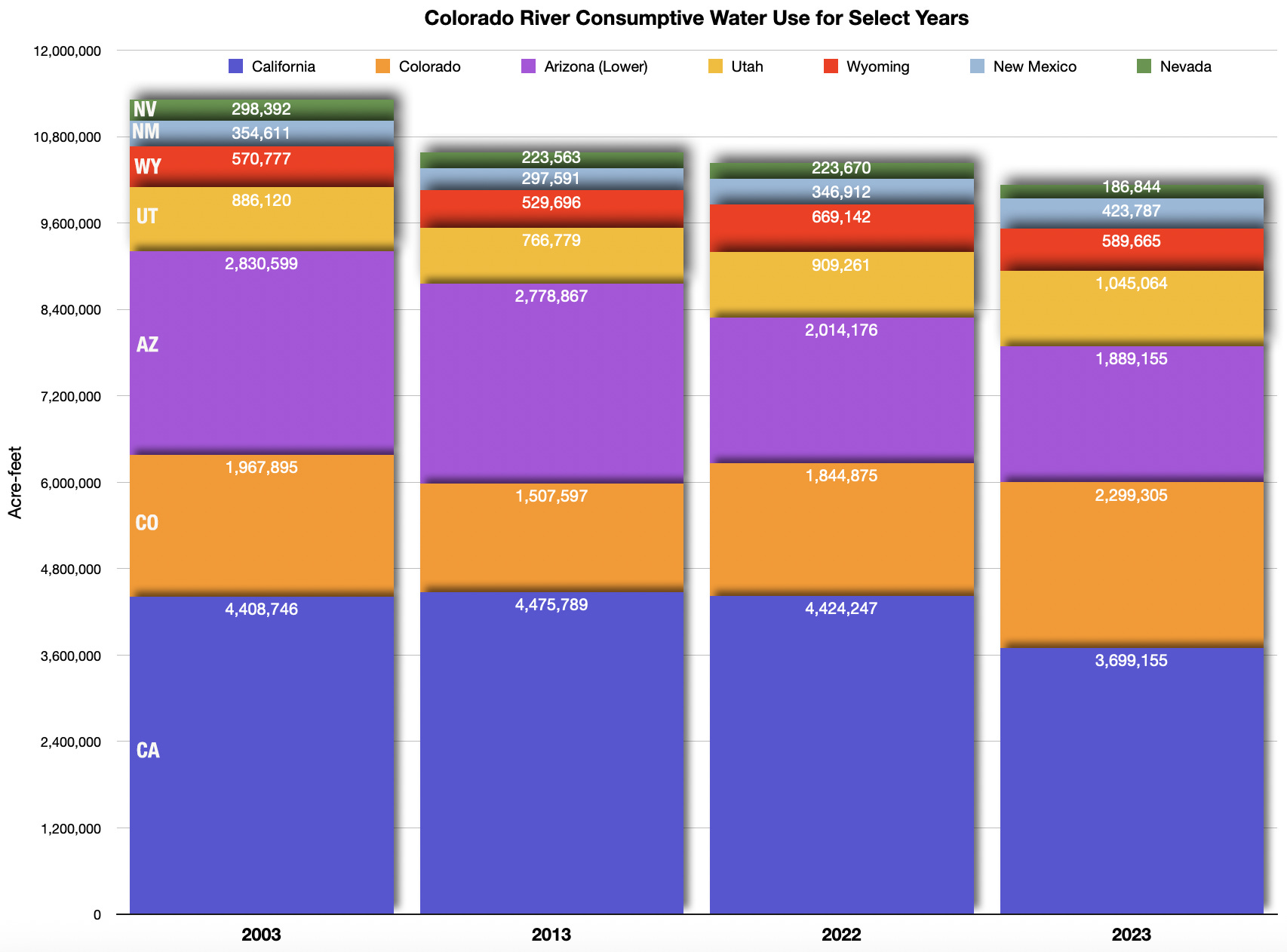

The Upper Basin (aka the Headwaters states) points out that while the Lower Basin has maxed out and even exceeded its Colorado River Compact allocation of 7.5 million acre-feet per year, the Upper Basin hasn’t even come close to using all of the water it’s entitled to. Furthermore, Upper Basin water users, especially those with more junior water rights, have grappled with drastic reductions during dry years because the Upper Basin lacks large reservoirs for storing water, meaning their water use is dictated in large part by the rivers’ flows. In 2021, for example, many southwestern Colorado farms had their ditches cut off as early as June, forcing them to sit the season out.

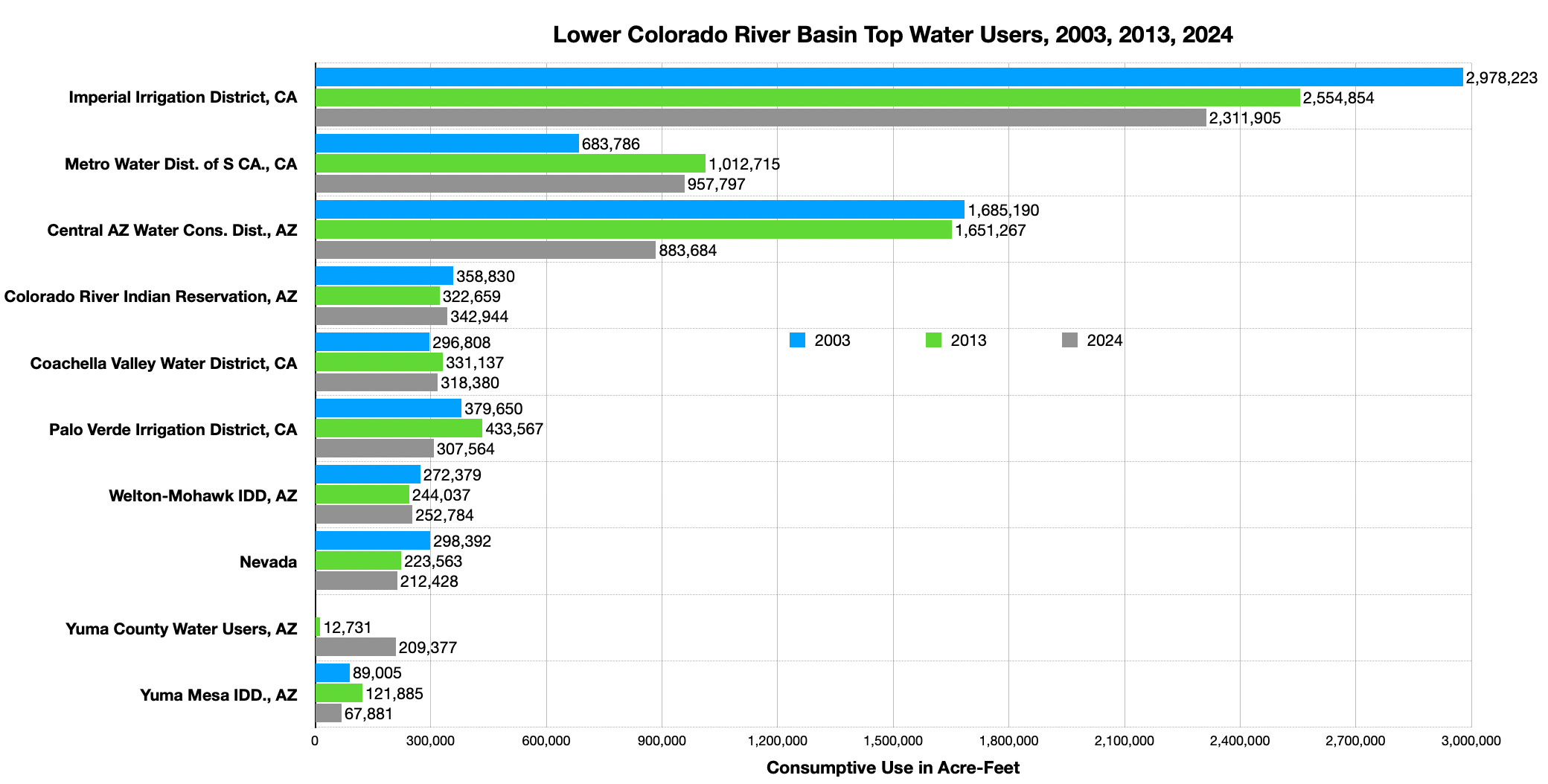

It’s also far simpler logistically to reduce consumption in the Lower Basin, where huge water users are served by a handful of very large diversions, such as the Central Arizona Project canal (which carries water to Phoenix and Tucson), the All-American Canal (serving the Imperial Irrigation District — the largest single water user on the entire river), and the California Aqueduct (serving Los Angeles and other cities), all of which are fed by Lake Mead and other reservoirs. Dialing back those three diversions alone could achieve the necessary water use reduction. The Upper Basin, on the other hand, pulls water from the river and its tributaries via hundreds of much smaller diversions; achieving meaningful cuts would require shutting off thousands of irrigation ditches to thousands of small water users under dubious authority.

Also, proposals to divert and consume more of the Colorado River’s water — such as the Lake Powell pipeline — remain on the table, albeit tenuously. If that project were to be realized, which is a big if these days, it would further drain Lake Powell and result in even less water flowing down to the Lower Basin.

Environmental groups tend to side with the Lower Basin on this issue. If the Upper Basin is forced to pull less water from the river, it would leave more water for the river, riparian ecosystems along the river, and aquatic critters. The Upper Basin’s proposal to release a percentage of the river’s “natural flow” from Glen Canyon Dam would leave less water in the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, possibly imperiling endangered fish and rafting.

Meanwhile, the states’ lack of consensus pushes Glen Canyon Dam closer to the brink of deadpool.

The BoR’s “Post-2026 Operational Guidelines and Strategies for Lake Powell and Lake Mead” offers five alternative scenarios for how to run the river. While it doesn’t give a “preferred” alternative, officials have indicated that without all of the states’ approval or congressional action, they are only authorized to go with the Basic Coordination Alternative. That would include a minimum annual release of 7.0 million acre-feet from Glen Canyon Dam, with the largest mandatory cuts being borne by Arizona. But according to the BoR’s latest 24 month projection, that release level would lead to Lake Powell’s surface level dropping below minimum power pool by the end of this year, which is a really big problem.

Back in 2022, as climate change continued to diminish the Colorado River’s flows and Lake Powell shrunk to alarmingly low levels, the dam’s operators were faced with the prospect of having to shut down the penstocks, or water intakes for the hydroelectric turbines, and only release water from the river outlets lower on the dam. Not only would this zero out electricity production from the dam, along with nixing up to $200 million in revenue from selling that power, it might also compromise the dam itself. “Glen Canyon Dam was not envisioned to operate solely through the outworks for an extended period of time,” wrote Tanya Trujillo, then-Interior Department assistant secretary for water and science, in 2022, “and operating at this low lake level increases risks to water delivery and potential adverse impacts to downstream resources and infrastructure. … Glen Canyon Dam facilities face unprecedented operational reliability challenges.”

In March 2024, a BoR technical decision memorandum verified and clarified those risks, and recommended that dam operators “not rely on the river outlet works as the sole means for releasing water from Glen Canyon Dam.”

The only way to do that is to keep the water level above 3,490 feet in elevation, which could mean shifting Glen Canyon Dam to a run of the river operation — where releases equal Lake Powell inflows minus evaporation and seepage — as soon as this fall. That, most likely, will lead to annual releases far below 7 million acre-feet, which will then lead to Lake Mead’s level being drawn down considerably as the Lower Basin states rely on existing storage to meet their needs, thereby threatening Lower Basin supplies. Such a scenario is clearly not sustainable, would put the Upper Basin states in violation of the Colorado River Compact1, and would almost certainly lead to litigation.

An irony here is that Glen Canyon Dam’s primary purpose is to allow the Upper Basin to store water during wet years and release it during dry years, enabling it to meet its Compact obligations. Hydropower, silt control, and recreation were secondary purposes. Now the need to preserve the dam could cause the Upper Basin to run afoul of the Compact. Aridification is rendering the dam obsolete, at least as a water storage savings account. Meanwhile, low levels are diminishing hydropower and recreation. It seems that soon, the dam’s main purpose will be to prevent Lake Mead from filling up with silt.

Mother Nature, or Mother Megadrought, if you prefer, has left few options for moving forward. The states still could come to an agreement, but it’s difficult to see how, given the long-running stalemate so far. The feds could reengineer Glen Canyon Dam to allow for sustained, low-water releases. That would only be a temporary fix, however, unless climatic trends reverse themselves and the West suddenly becomes much wetter and cooler. Somehow, that doesn’t seem too likely.

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

Is all of this Colorado River talk a bit confusing? Do you find yourself lost in the water-wonk weeds? Yeah, me too. That’s why I put together the Land Desk’s Colorado River glossary and primer. It’s not behind the paywall yet, so even you free-riders can take a look for the next few days. It’s worth looking at even if you already received the email edition last month, because it is now updated with new terms and more graphics (it didn’t all fit in the email version). I’ll keep updating it, too, as new questions about what it all means come up. And if you’re not already, you should consider becoming a paid subscriber and break down the archive paywall, allowing you to read the whole list of analysis, commentary, and data dumps I’ve done on the Colorado River over the last five years.

The Upper Basin and Lower Basin generally disagree on how to interpret the Colorado River Compact’s provision dictating that the Upper Basin “not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 million acre-feet” for any 10-year period. The Upper Basin sees it as a “non-depletion obligation,” meaning they can’t exceed their 7.5 MAF/year allocation if it causes the Lee Ferry flow to fall below a 7.5 MAF/year average. The Lower Basin believes it’s a “delivery obligation,” and that the Upper Basin must deliver 7.5 MAF/year no matter what. Which interpretation is correct determines whether run-of-the-river would violate the Compact or not.