Monarchs are in trouble (the butterflies, I mean)

Grazing group tapped to monitor ... grazing; Messing with Maps 1857 edition

🦫 Wildlife Watch 🦅

The monarchs are struggling — as in the butterflies, not kings and queens.

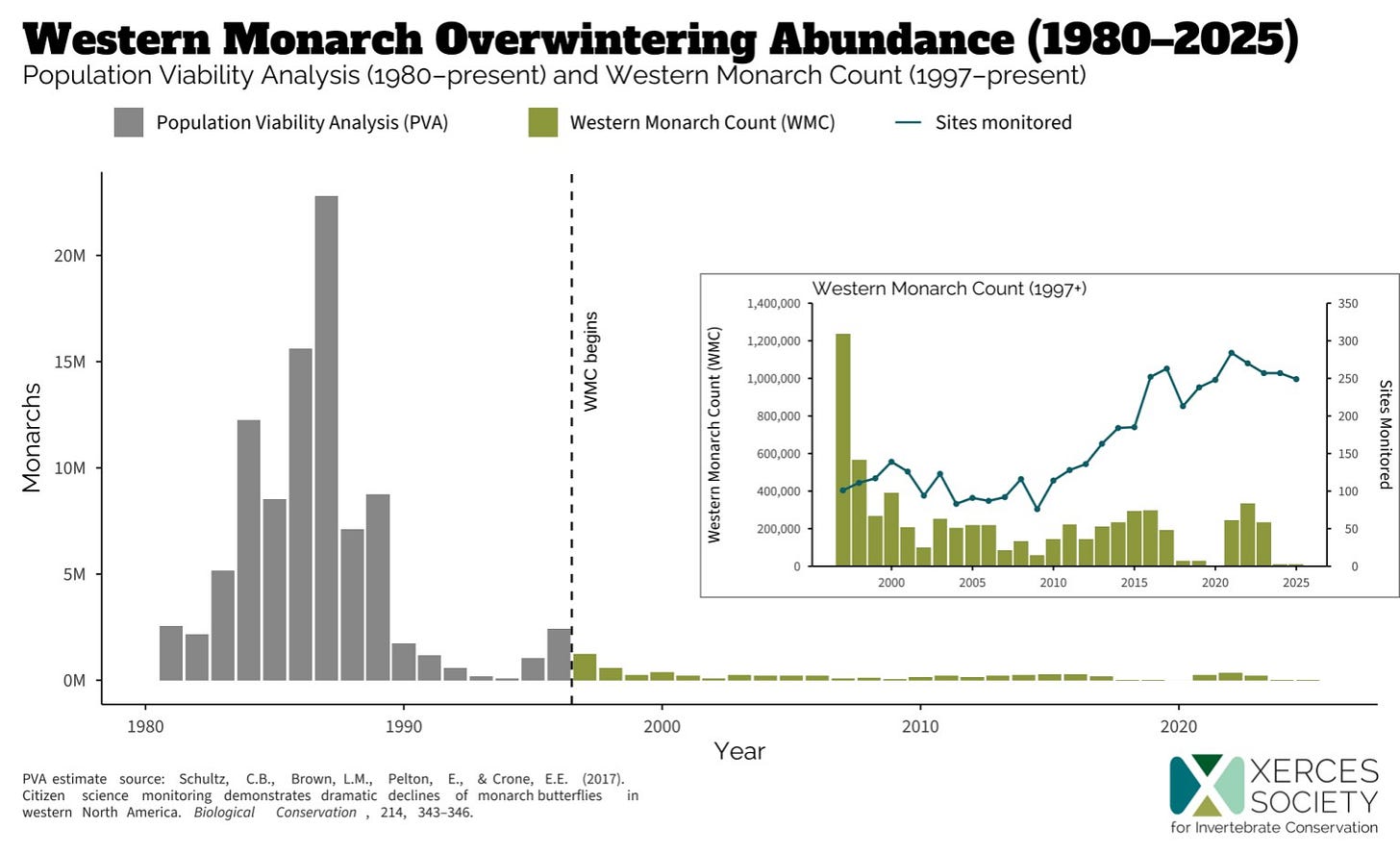

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation is reporting that last year’s annual Western Monarch Count revealed historically low populations of the iconic butterfly. Only 12,260 monarchs were recorded across 249 sites along California’s coast during in late November and early December 2025, which is typically the peak overwintering period.

This is the third lowest tally since the count began in 1997, after 2020, 2024, and 2025. In the 1980s, monarchs numbered in the millions. “Western monarchs are in serious trouble. The migration is collapsing,” said Emma Pelton, a senior conservation biologist with the Xerces Society, in a written statement. “We must move quickly to safeguard existing monarch habitat and restore and better manage the landscapes monarchs depend on, or else we risk losing one of North America’s most incredible natural phenomena.”

The urgency has apparently been lost on the Trump administration, which in December delayed a decision to extend federal endangered species protections to the butterfly. Now, the Center for Biological Diversity is suing the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over the delay, and seeks to force the agency to set a binding date to finalize protections.

Monarchs face myriad threats, including human development, herbicide-exacerbated milkweed decline, deforestation, and climate change.

If you see a monarch, consider adding it to the monarch milkweed mapper (you can also use the map to see sightings near you).

Back in the Land Desk’s early days I wrote a little essay about monarch abundance in the Animas Valley near Durango and how we would capture the caterpillars and watch them transform into butterflies (before releasing them, of course) in my first grade class. You can read it by clicking the link below — if you’re a paid subscriber. If not, you can sign up for a month or a year and not only access all of the archives, but also get that warm feeling from supporting a good cause!

🐓 Regulatory Capture Chronicles 🦊

Earlier this month, the Bureau of Land Management and the Public Lands Council signed a memorandum of understanding allowing livestock operators to work with the agency to monitor grazing allotments on public lands.

At first glance, this sounds like a good idea: The BLM has long failed to adequately assess rangeland health — let alone enforce standards — and the Trump administration has further diminished the agency’s staff, making their task even more difficult. So, why not bring in some help, especially if it includes folks who spend so much time on the land that needs monitoring?

If it’s carried out properly, the deal could benefit the lands. But given the players here, I’m a bit skeptical. See, the Public Lands Council is not looking out for public lands, despite the friendly sounding name. They are the lobbying organization for public lands livestock operators (and walk hand-in-hand with the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association). More than a simple trade organization, however, they are also driven by a right-wing ideology and regularly push back on public lands protections, even if they don’t affect grazing.

For example, the PLC is generally opposed to new national monument designations, and came out vehemently against the establishment of Bears Ears National Monument in 2016. This in spite of the fact that neither the original designation, nor the Biden-era restoration of the 2016 boundaries and management plan, curtailed grazing in any shape or form. In fact, by precluding new oil and gas and mining development, the monument protections could actually benefit livestock operators.

In other words, bringing the PLC on to monitor grazing’s effects on public lands is like asking the American Petroleum Institute to monitor the oil and gas industry’s impacts on the land, air, and water. It doesn’t seem too smart, unless the goal is to hand public lands over to the extractive industries. Hmmm…

***

Well how about that! The 2026 federal land grazing fee has increased for the first time in years, going from the minimum $1.35 per AUM to a whopping $1.69. That means, beginning next month, livestock operators will pay $1.69 per month for every cow-calf pair (or one horse or five sheep or goats) that munches on Bureau of Land Management of Forest Service forage. For the record, that’s still more than ten times less than what they would pay on most state or private land, meaning public lands grazers are being subsidized. The price went up partly in response to increasing beef prices, which have soared over the last year.

⛏️ Mining Monitor ⛏️

Acid mine drainage and rock drainage are pernicious problems that plague the West’s mineralized regions. And there are no straightforward fixes. As long as water and oxygen come in contact with sulfides, which happens both in mines and in un-mined areas, sulfuric acid is likely to form. The acidic water will then dissolve naturally occurring minerals, including toxic heavy metals, and carry them downstream, affecting aquatic life. The only reliably effective solution is to treat the water in perpetuity, an expensive process that tends to produce huge volumes of sludge that must be disposed of.

Researchers at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research have not found a cure for acid mine drainage. But they have found a way to glean something valuable from the waters being treated besides, well, sludge. University of Colorado professor Diane McKnight and her colleagues have found that many streams in the state’s Mineral Belt contain high concentrations of rare earth metals that are used in hi-tech applications, like smart phones and electric vehicles. And now they’re working with other researchers and an Energy Department grant to develop a method for “extracting high-value and strategically important rare earth elements from domestic mining waste streams.”

If the method can extract the materials at marketable quantities, then it could possibly be used to offset the costs of mine drainage treatment.

Primer: Acid Mine Drainage

Acid mine drainage may be the perfect poison. It kills fish. It kills bugs. It kills the birds that eat the bugs that live in streams tainted by the drainage. It lasts forever. And to create it, one needs no factory, lab, or added chemicals. One merely needs to dig a hole in the earth.

🗺️ Messing with Maps 🧭

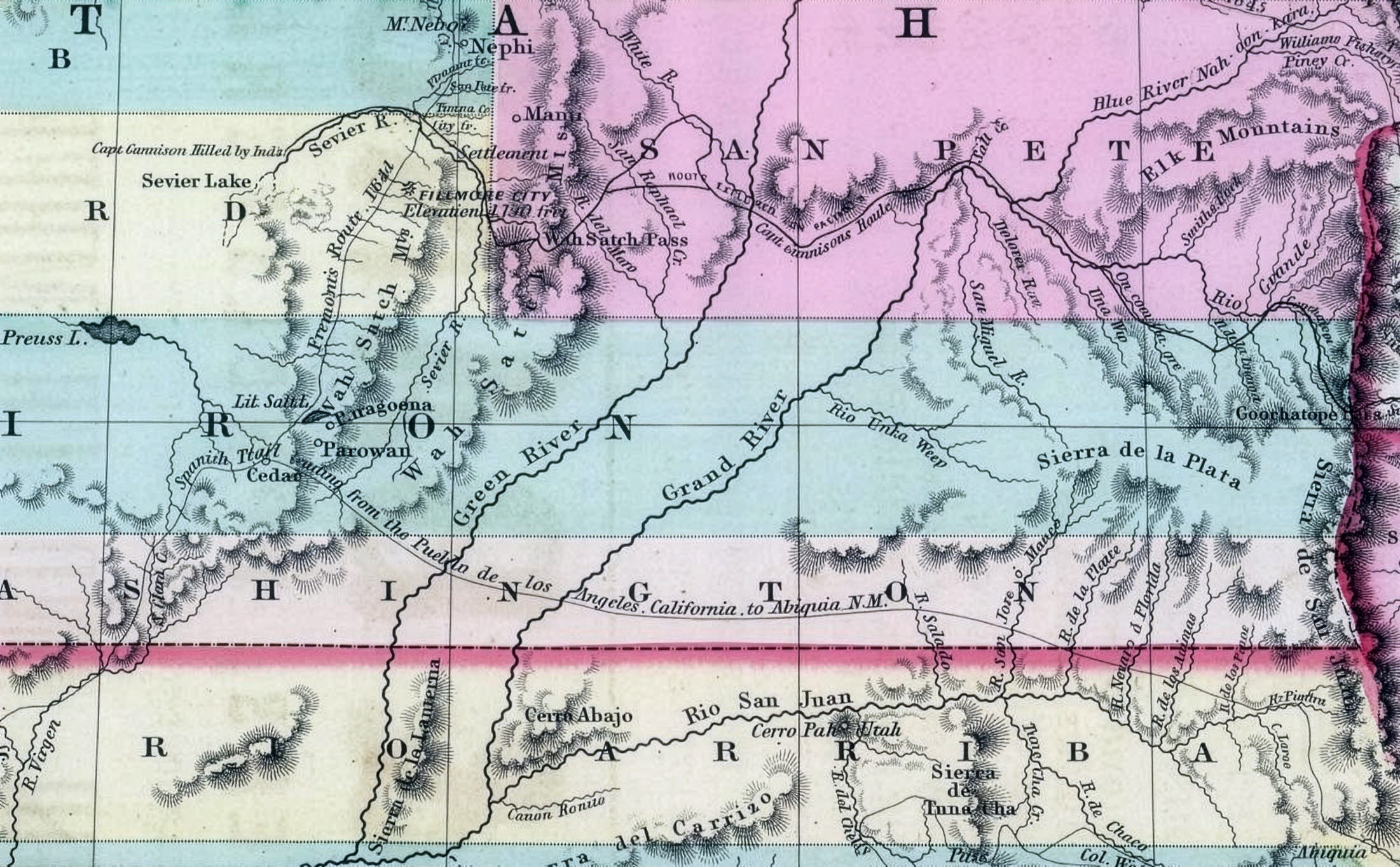

This is a cool one from 1857, when Colorado was still part of the Utah and New Mexico territories. Note the different names for the Colorado River: It’s the Blue (Nah-aon-kara) above the confluence with the Gunnison (which on the map is called Rio Grande), then it becomes the Grand below the confluence, and finally is called the Rio Colorado after it joins up with the Green. The Dolores and San Miguel rivers appear to be reversed, and there’s something called the Rio Unka Weep, which might refer to McElmo Creek? Over on what is now the Nevada-Utah border is a Preuss Lake, which I cannot find anywhere on modern maps, so I’m guessing it was more legend than lake. And the Green/Grand confluence shows up way down by what is now Page, Arizona. I’m curious about how this error came about: Did someone mistake, say, the Escalante River for the Green?

Parting Poem

LOCAL KNOWLEDGE by Richard Shelton from Selected Poems, 1969-1981, University of Pittsburgh Press on December nights when the rain we needed months ago is still far off and the wind gropes through the desert in search of any tree to hold it those who live here all year round listen to the irresistible voice of loneliness and want only to be left alone local knowledge is to live in a place and know the place however barren some kinds of damage provide their own defense and we who stay in the ruins are secure against enemies and friends if you should see one of us in the distance as your caravan passes and if he is ragged and gesturing do not be mistaken he is not gesturing for rescue he is shouting go away