Vanishing butterflies and solar scuffle

News Roundup: New study pegs butterfly decline on climate change and Nevada solar project gets Double Negative reviews.

More than four decades later, the image is still clear in my memory: The sun shines through the big windows of the first-grade classroom at Needham Elementary. As a statuesque Ms. Ritchey stands at the front of the room, patiently guiding us through the day’s lesson on cursive, I look over at the gallon-sized milk jar and nearly fall out of my seat. There, on the milkweed inside the jar, sits an unfurled, still moist-looking, brand new monarch butterfly.

“Look! Look! Ms. Ritchey, the butterfly! It hatched!”

A couple of weeks earlier, my parents and I had gently plucked a stalk of milkweed—black-, white-, and yellow-striped caterpillar attached—from the floodplain below my grandparents’ Animas Valley farm, put the plant and caterpillar in the milk jar, and taken it to school. Perched upon the windowsill, the jar gave us youngsters a front-row view of the transformation, from bizarre-looking caterpillar to cocoon to chrysalis to the fragile and lovely creature that now sat perched on the milkweed, interrupting our cursive lessons.

So it was a punch to the gut to learn that today’s first graders are far less likely to be able to witness this marvel, and that the next generation may be deprived of it altogether. That’s because butterflies are vanishing from the Western United States, according to a study published in Science this month. While the monarch’s decline has been on researchers’ radars for years, this study shows that the woes extend to all varieties of butterflies. The study’s authors, led by M.L. Forister, found that since 1977—the year that my classmates and I watched the monarch metamorphose—the number of butterflies has plummeted at an estimated rate of 1.6 percent per year.

While pesticides and development-related habitat-degradation may be factors in the decline, the primary cause appears to be climate change, particularly warming autumn temperatures and decreasing summer rain. Summer temperature hikes actually increase numbers, but a warming temperature during the fall, according to the study, “likely induces physiological stress on active and diapausing stages, reduces host plant vigor, or extends activity periods for natural enemies.”

Climate change is just the latest in a list of threats to the beleaguered and iconic monarch. The deep orange and black insect migrates northward from Mexico each spring before returning south for the winter, and wildlife researchers on both sides of the border report that the butterfly is in trouble. The Xerces Society Western Monarch Count, which focuses on California, has documented a 99 percent decrease in monarch populations since the 1980s. In December of last year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that an endangered species listing is warranted for the butterfly, but declined to list it due to the need to focus limited resources on more gravely threatened species.

Monarchs depend heavily on milkweed—it’s one of the only plants the caterpillars eat and the only place the butterflies lay eggs—and milkweed is disappearing. According to 2017 U.S. Geological Survey research, the nation lost 862 million milkweed plants between 1999 and 2014, depriving the butterfly of a big chunk of its sustenance. Milkweed has fallen victim to the herbicide glyphosate, more commonly known as Roundup, the use of which has surged since the development of Roundup-resistant crops over the last couple decades. Milkweed is poisonous to sheep and cattle, as well, so ranchers have long tried to rid their pastures and grazing areas of the stuff.* Glyphosate makes the job a lot easier.

Glyphosate is likely just one of a host of culprits, however. Using museum records, researchers found in 2019 that milkweed and monarchs began their decline in the 1950s, long before Roundup hit the market, thereby sparking vigorous scientific debate. That timing would suggest that postwar urbanization, loss of farmland, and industrialization could be to blame. The notorious insecticide DDT also enjoyed its heyday in the forties and fifties, which surely affected the butterflies (albeit not the milkweed, since DDT kills bugs, not plants).

All I know is that when I was in first grade, butterflies, most noticeably the big, striking, yellow swallowtails and the Halloween-colored monarchs, were abundant in the Animas Valley north of Durango. Literal swarms of swallowtails gathered around mud-puddles and my parents never would have allowed me to capture a caterpillar and take it to class if it were rare or imperiled.

It’s remarkable that there were any bugs around at all given the ubiquity of pesticide use back then. My mom tells me that my grandfather used to come home from working with the local mosquito control district, his clothes literally soaked through with DDT (which was also put in paint, on wallpaper, and insect repellent). When DDT was banned in 1972, the mosquito folks switched to something else nearly as nasty, with which I had a number of close encounters. On many a lilac-hued summer evening, my cousins and I would play out in the ditches, only to be interrupted by the high-pitched buzz of the malathion truck moving slowly down the Old Highway, misting poison into the air. But we’d wait to run inside, wait for the bellowing voices of multiple aunts hollering into the dusk: “Get inside RIGHT NOW!”

After that long-ago chrysalis morphed into a monarch, my classmates and I carefully took the milk jar outside. It was a warm day and the leaves of the cottonwoods along Junction Creek quaked in wind and sunlight against the bright blue sky. We opened the jar and stood back and watched with wonder as the monarch tentatively flapped its wings, lifted its body up out of the mouth of the jar, and flittered away on the summer breeze.

“Saving an iconic butterfly is important and would help us sustain beauty, wonder, and majesty in nature,” wrote Anurag A. Agrawal, a professor of environmental studies at Cornell University, in 2019. “But for me, the concern is much larger than a single species. Monarchs are sentinels, traversing the continent and tasting their way as they move. Thus, to understand what is happening to environmental health more generally, monarchs may be a source of information for both our own population and biodiversity writ large.”

Help keep track of milkweed and monarchs across the West and report your sightings to the Monarch Milkweed Mapper.

*Cattle and sheep won’t eat milkweed unless other forage is scarce. But in the overgrazed West, good forage can be hard to find.

***

The News: A motley coalition that includes skydivers, off-roaders, and art aficionados has risen up to oppose a proposed solar-power facility in southern Nevada.

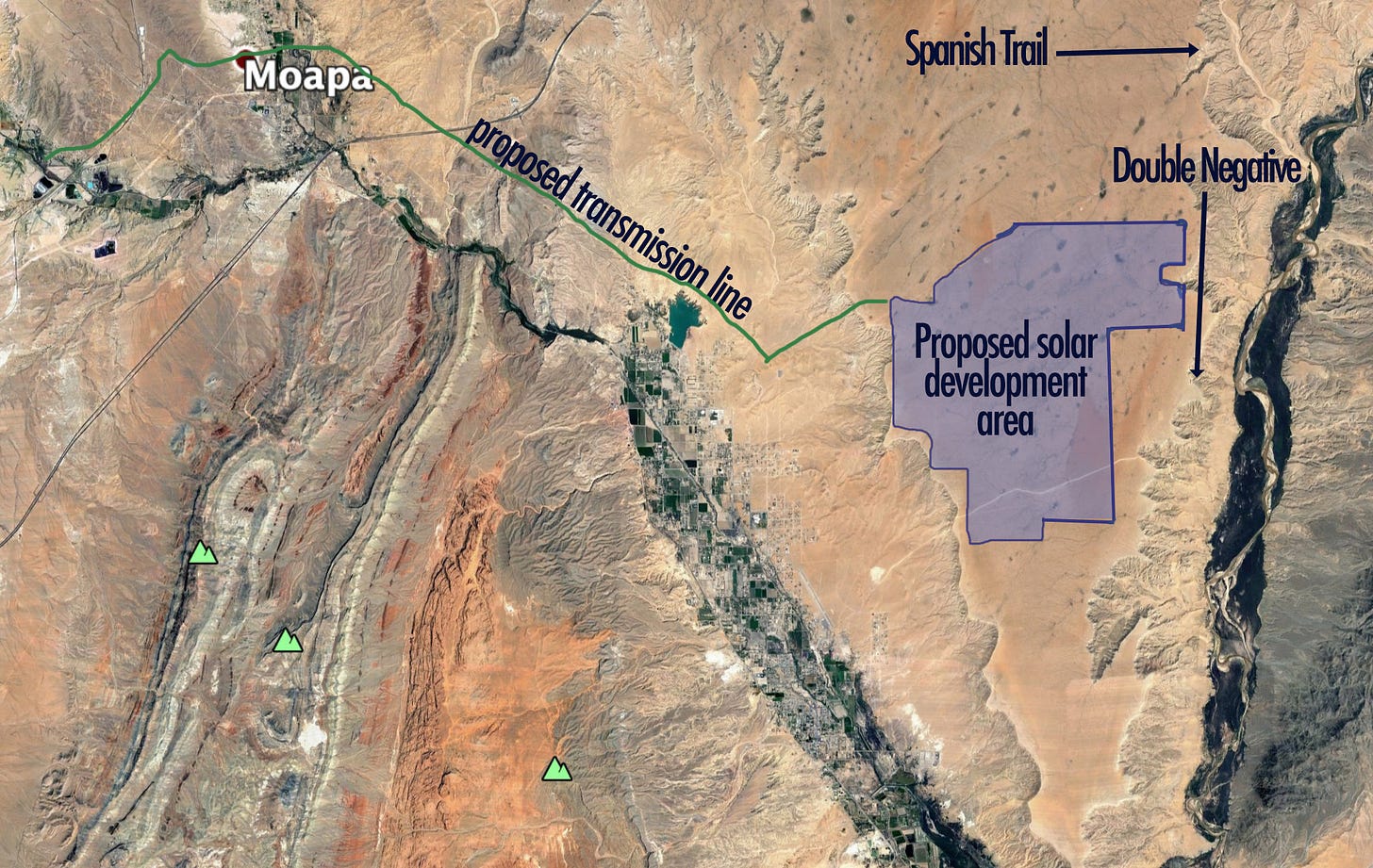

The Context: To the passerby on I-15, Mormon Mesa must look like the perfect place to put a solar array. The mesa top, which from the air resembles a massive bird beak that rises up between the Virgin River and the Moapa Valley, is sunny, nearly perfectly flat, sparsely vegetated, managed by the Bureau of Land Management, and has transmission lines leading out of the defunct Reid Gardner coal power plant nearby.

But there is far more here than meets the untrained eye. The calcified soil that caps the mesa took 2 million years to form, and is now home to desert tortoises, Gila monsters, and other wildlife. This is part of the homeland of the Nuwuvi, or Southern Paiute people. The Spanish Trail crosses the mesa. In 1952, beings from the planet Clarion landed their giant space “skows” on Mormon Mesa, or so said a guy named Truman Bethurum, who claims to have conversed with the Clarionites there.

Then, in 1970, an artist named Michael Heizer showed up, gouged two deep trenches into the mesa’s edge, and called it Double Negative, thereby creating one of the first, big, non-ephemeral pieces of land art. Ever since then, art lovers have been making pilgrimages to Mormon Mesa to see Heizer’s masterpiece, crossing paths with the commercial skydiving service clients who land there, with guided OHV trips and dirt bike races, Spanish Trail history buffs, and locals and tourists taking advantage of the unblemished and spectacular view.

Now a lot of those folks are concurrently rising up to fight a proposal by Arevia Power to build an 850-megawatt photovoltaic power facility that would span 9,200 acres on the mesa.

Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak urged the BLM to fast-track the permitting process in order to get more clean energy into the grid and for the hundreds of construction jobs it would create. But locals are not so enthused. The jobs would mostly go to non-locals and the project would blemish views, block access to off-roaders and possibly the skydivers, and would be situated just a stone’s throw from Double Negative. While most environmental groups have been quiet on the proposal, thus far, Basin and Range Watch has vocally joined the opposition. But other groups may join in as the permitting process, which is in the nascent phase, moves forward.

While the players may be a little different than with other such battles, this sort of fight—with desert-defenders going head-to-head with utility-scale solar—is likely to become more common, particularly with the Biden administration pledging to fast-track renewable energy development on public lands.

On a slightly tangential note, here’s an old video I made about Double Negative, Mormon Mesa, and land art:

(Thanks to Sammy Roth and his Boiling Point newsletter for tipping me off to this one, and to probably the first time Art Newspaper covered a solar installation fight).

***

After a bleak start to winter, snowfall-wise, across much of the West, things started looking up in February, as a series of storms pounded the mountains. But in most places it was too little, too late, and hopes of a spring recovery and relief from the drought are dimming. I’ll give a deeper look into the snowpack situation in early April. In the meantime, it’s looking more and more like we’re in a permadrought, i.e. an extended period of aridification:

***

WHAT THE LAND DESK IS READING

The Arizona Republic has a good story from Debra Utacia Krol about the recent unearthing of a Hohokam site in Tempe and what it reveals. The Hohokam (or Huhugam) people built a massive canal system in what is now Phoenix. Many of today’s canals are essentially the ancient ones, repurposed.

And Rico Moore writes in Audubon about what it will take for the Biden administration to put the Bureau of Land Management back together again after it was dismantled by Trump. Naming Rep. Deb Haaland, of the Pueblo of Laguna, is a good start (her confirmation is pretty much assured in the not-too-distant future), particularly in combination with other top-level appointments, all of whom are stark contrasts to the previous administration’s appointees.

p.s. If you have trouble seeing any of the images or graphs above, please click through to the web version, where photos are displayed at a higher resolution.