When "disposing" of public land isn't the end of the world

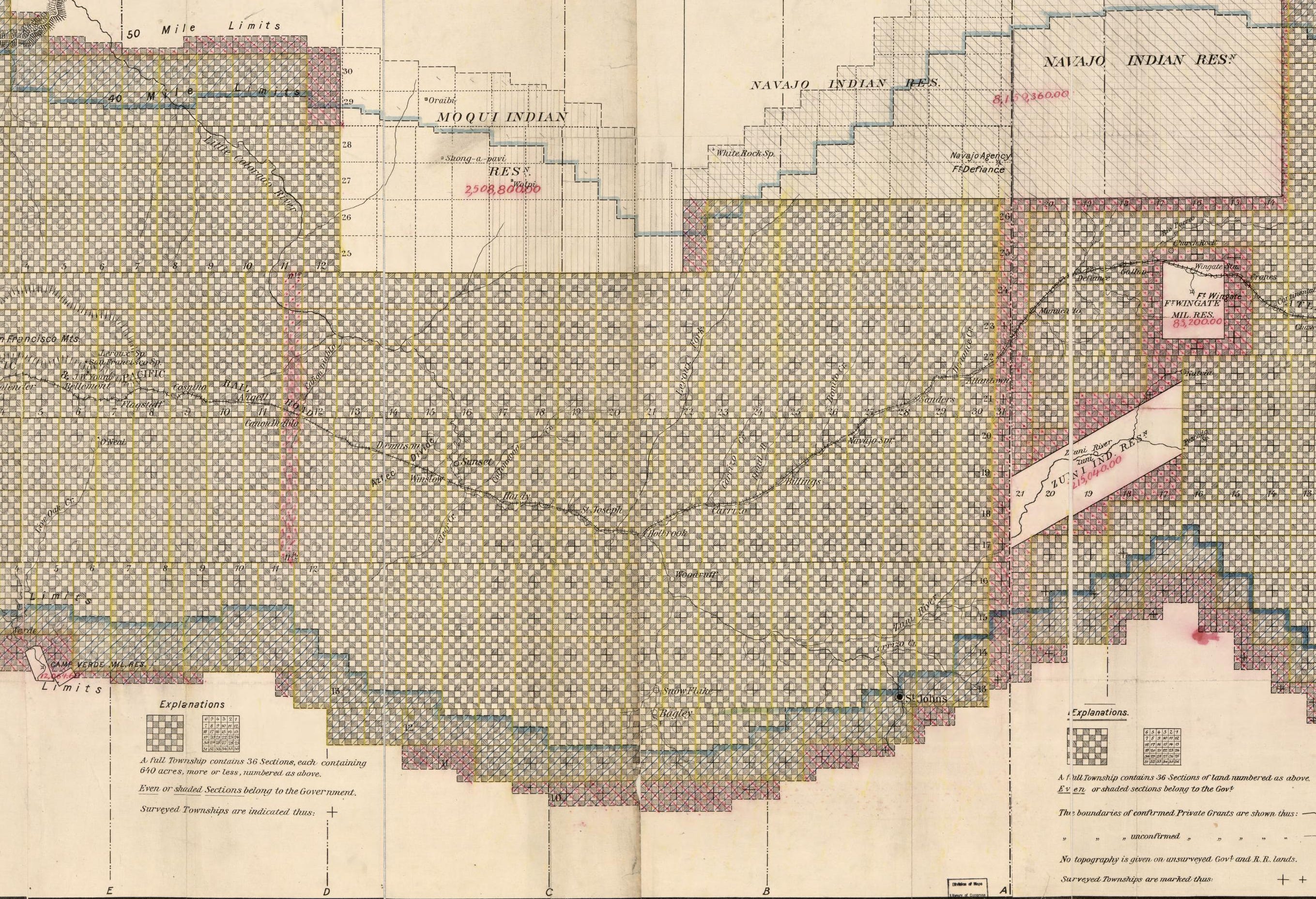

🌵 Public Lands 🌲

The debate over selling off public land has become more serious, and consequential, than ever. While the urge to transfer public land out of the American public’s hands has flared up many times over the last century or so, never has the concept ga…