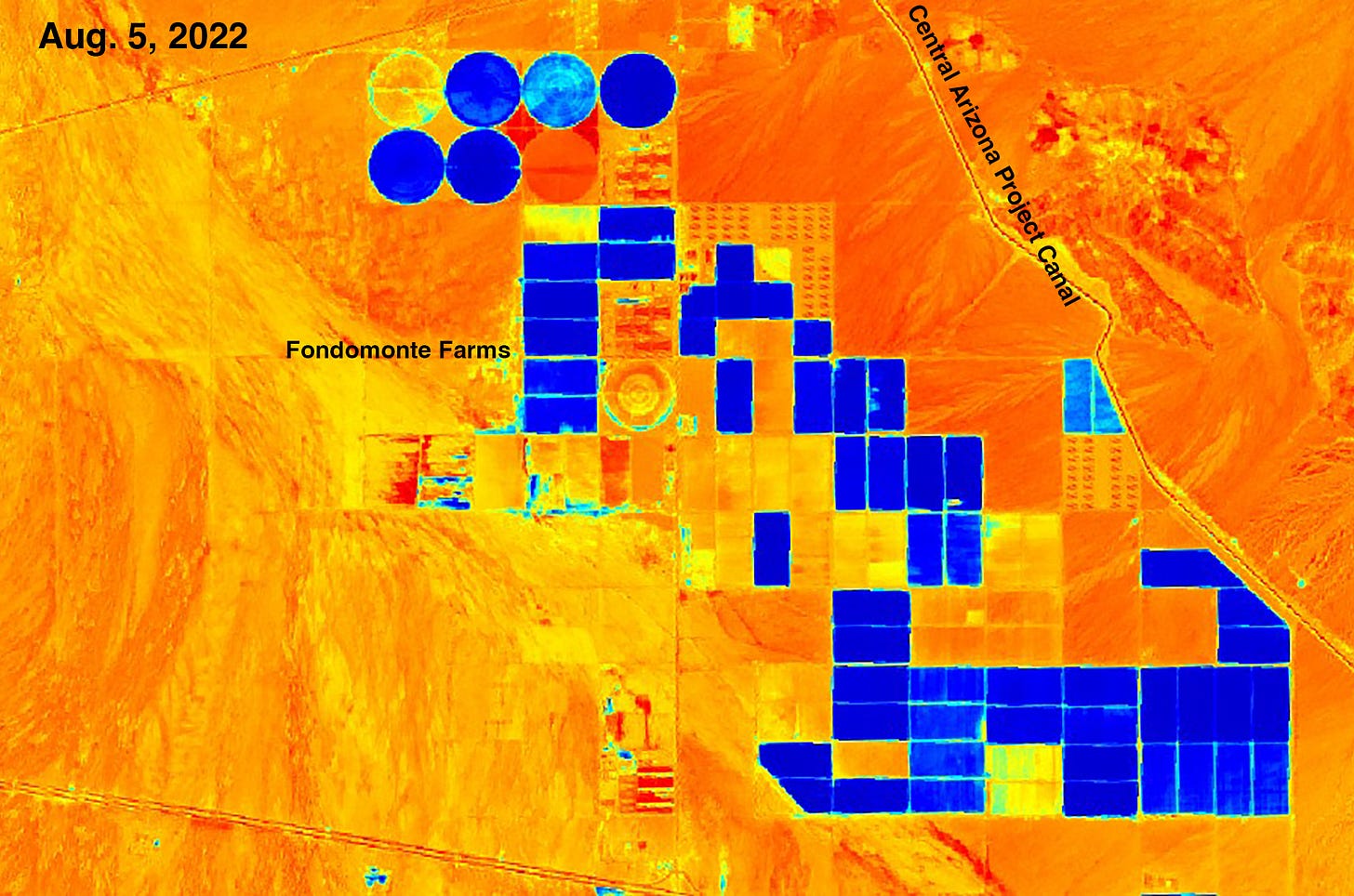

Visualizing aridity -- from space

Satellite images of vegetation and moisture from around the West

How does the saying go? “Give a guy a map and he’ll peruse for a day; give a guy Google Earth and he’ll waste his life away.” Something like that. Anyway, I’m Mr. Land Desk, and I’m a satellite map addict. I love the the things and could spend days—and sometimes have—virtually exploring mountains, deserts, and cities. Even more addicting are the layers …