Think like a watershed: Interdisciplinary thinkers look to tackle dust-on-snow

Cortez symposium focused on solutions

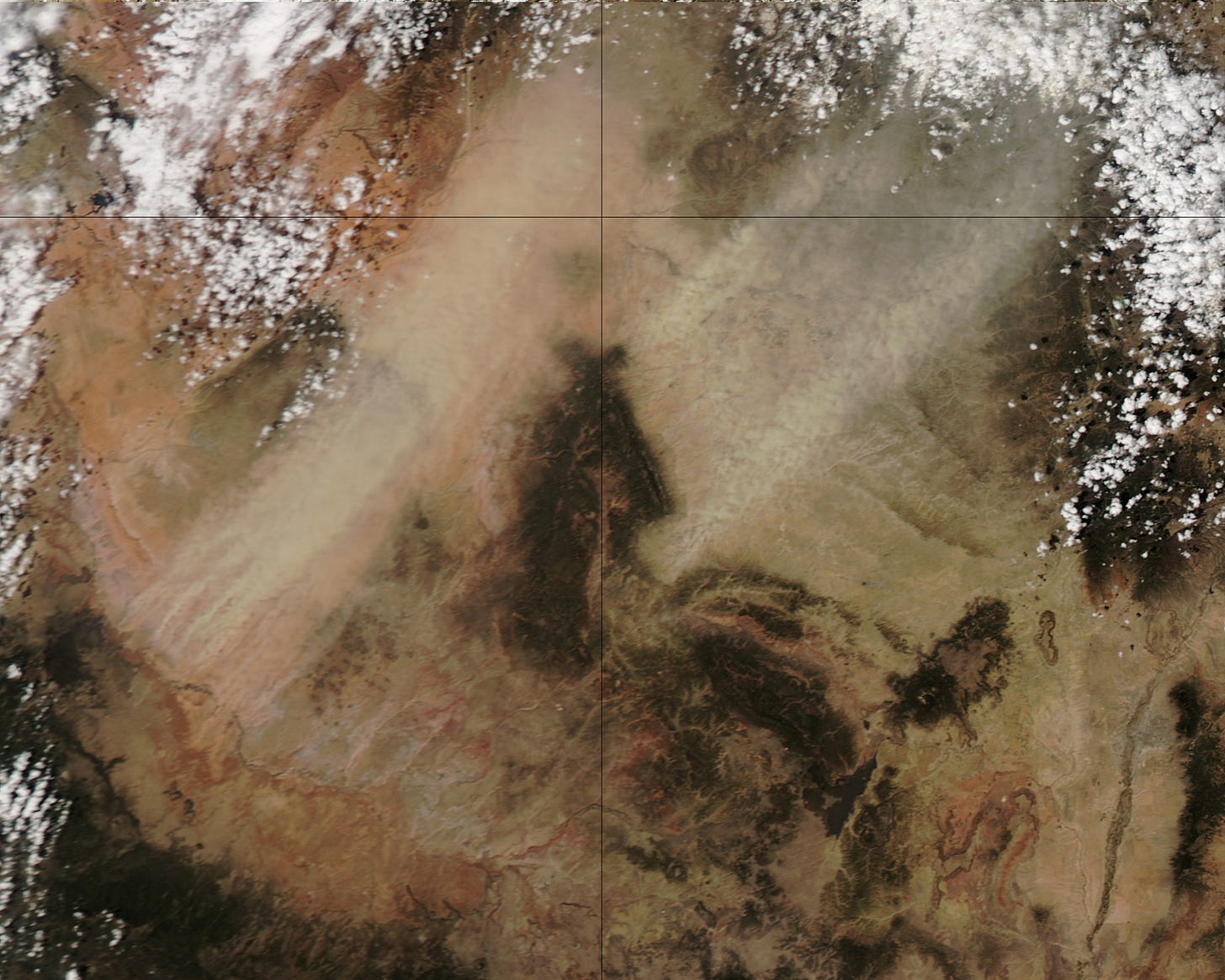

🥵 Aridification Watch 🐫

I must admit that when I was invited to attend a symposium in Cortez, Colorado, focused on dust on snow, I was a bit hesitant to accept. Six hours of talking about dust and snow? I …