The West's Sacred Cow

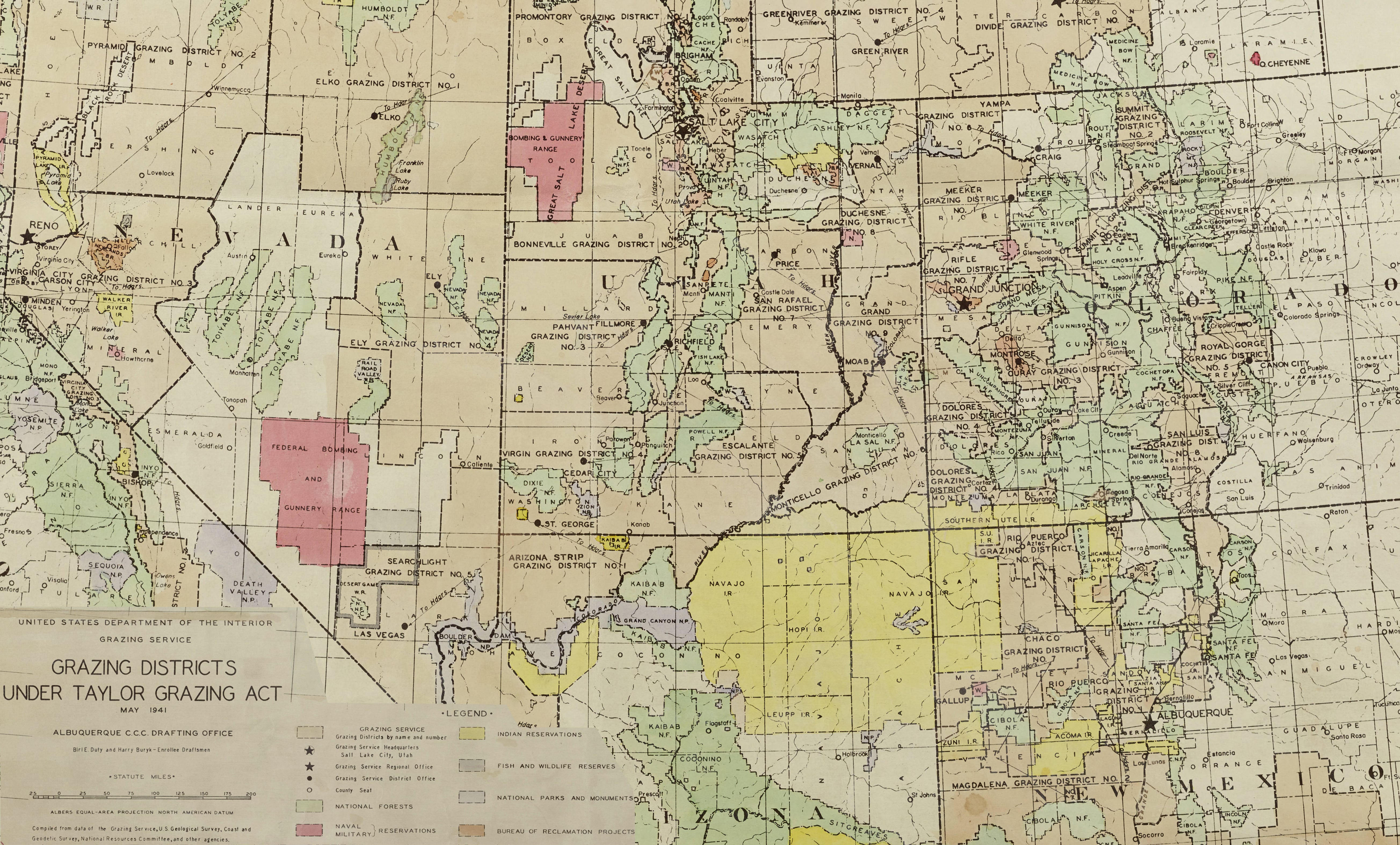

Public land grazing makes it through another administration unreformed

🌵 Public Lands 🌲

“The vast San Juan ranges, with a plentiful supply of choice feed, were not to remain such for many years. Like everything else that goes uncontrolled or without supervision these ranges were used selfishly with the present only in mind [leaving them] in an almost irreparable condition.”

—Franklin…