The arrogance of the off-road vehicle lobby

Also: Aridification Watch; Mining Monitor

In a rather predictable — but still maddening — move, the off-road-vehicle lobby is suing the Bureau of Land Management over the agency’s Labyrinth Canyon and Gemini Bridges travel plan for off-highway vehicle use.

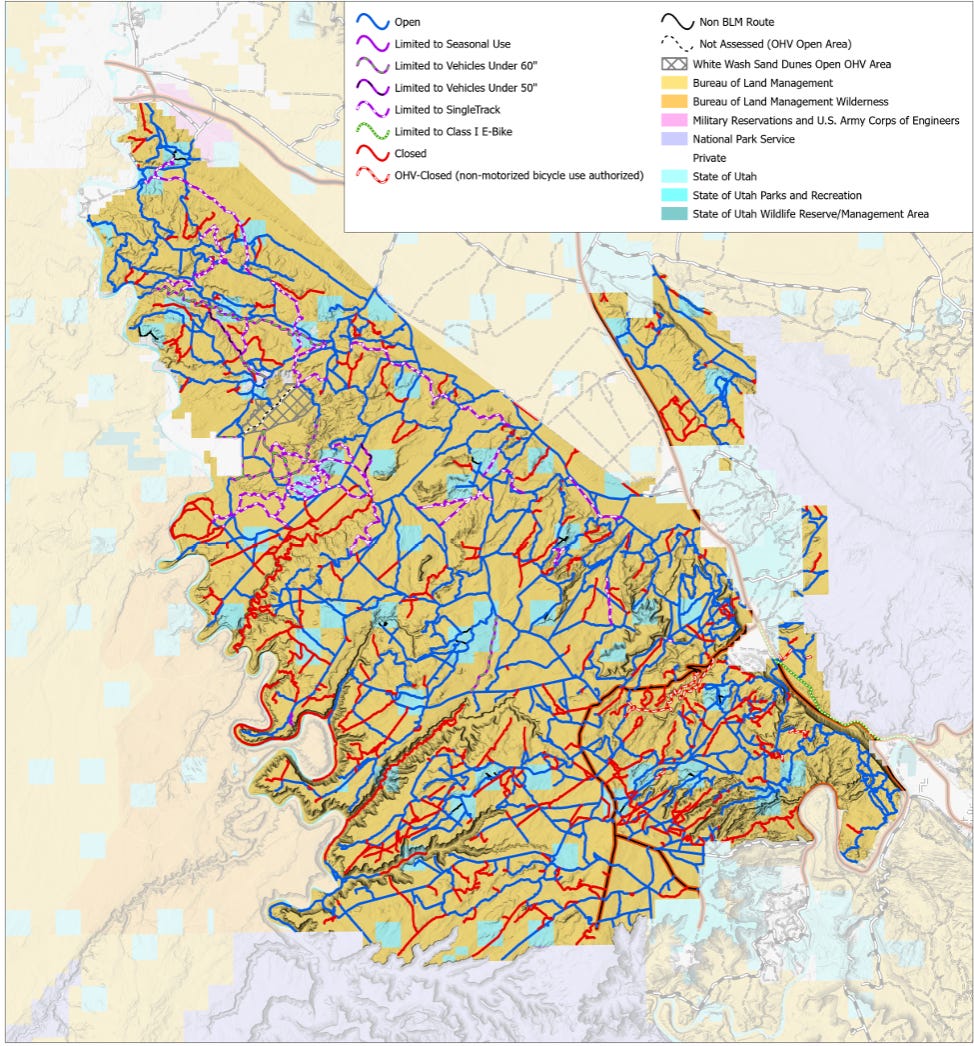

The BlueRibbon Coaltion, Colorado Off-Road Trail Defenders, and Patrick McKay are challenging the “illegal and arbitrary” closure of 317 miles of motorized routes on about 468 square miles of public land north and west of Moab between the Green River and Highway 191. The off-road coalition was already shot down once by the Interior Board of Land Appeals; now they’re taking their gripes to federal court, using the same spurious arguments.

Of course, these groups have every right to challenge federal agencies’ decisions; environmentalists do it all the time. But what’s maddening about these motorized-access groups is their intransigence — even arrogance — and stubborn unwillingness to compromise. They promise to “Fight for Every Inch” of motorized access to public lands, not for any real reason but as an end in itself, damn the consequences to the environment, the public, and wildlife.

The kerfuffle over the Labyrinth/Gemini plan is a perfect example.

Over the last couple of decades, vehicle traffic — and the impacts — have burgeoned on some 1,100 miles of motorized routes in the management plan’s area. The type of traffic has changed, too, shifting from the relatively slow-going and quiet jeeps and SUVs to the dune-buggyesque side-by-sides that have become increasingly popular in recent years. They go faster, are noisier, and kick up more dust than other vehicles. They also carry more people into the backcountry than a motorcycle or old-school ATV, thus multiplying the adverse effects.

For years, river runners, public lands advocates, and local residents and elected officials have been pushing the agency to get a handle on the traffic on the 300,000-acre slickrock expanse. Last year, the BLM came up with four alternatives, ranging from keeping the status quo to closing up to 437 miles of trails. Yes, the strictest alternative would have closed less than half of the routes to vehicles, leaving almost 700 miles open to some form of motorized travel. In other words it was a compromise that favored the motorized crowd.

But even that went too far for the BLM, which ultimately shut down just 317 miles of motorized routes, while limiting motorized travel (to motorcycles or smaller ATVs, for example) on 98 miles. In other words, you can still burn gasoline and spew exhaust on more than 800 miles of routes on this one relatively small swath of public land. Meanwhile motorized travel remains mostly unrestricted on more than 10,000 miles of roads, two-tracks, and old trails in southeastern Utah.

That’s not enough for the BlueRibbon Coalition and friends, however; it’s never enough for them. They are ideologically opposed to decommissioning even the most insignificant road spur, and they and their allies in local and state government will squander millions of taxpayer dollars to fight the closures. Their reasoning? Because OHV recreation is, in the words of the lawsuit, “a way of life in the American West.”

Really? I mean, it’s the same trope rolled out whenever someone tries to get a coal plant to stop belching pollution all over folks or a mine to stop defiling the streams. In those instances it may have some validity: The move could affect the miners’ or the coal plant workers’ livelihoods, and therefore their way of life. But these folks will still be able to ride their noisy machines around on hundreds of miles of roads. Believe me: Nothing about this plan will affect their way of life.

I highly doubt the motorized coalition will prevail; even the most conservative judges are unlikely to fall for their faulty legal reasoning. And so, the plan likely will remain in place, as it should. It’s a compromise, and an admittedly crappy one for those of us who would like to see a lot fewer vehicles — and people — trampling the landscape. After all, it still leaves the sprawling road network mostly intact. But maybe it’s the best we can expect, and at least it does something. And it will make it just a little easier for the quiet users, the bighorn sheep, the coyotes, and the silence to find a bit of refuge from the incessant whirr of combustible engines and the humans driving them.

🔥 Aridification Watch ☄️

I hate to start out the New Year with kind of grim news, but it’s sure not looking good out there as far as snow goes. In fact, many parts of the West are experiencing one of their thinnest Jan. 1 snowpacks in the last two decades. And the last two decades, as you probably now, were generally lousy.

A dearth of precipitation is the main problem, of course, but abnormally warm temperatures aren’t helping matters. And remember, “normal” is based on the three decades between 1991 and 2020, which was a heck of a lot warmer than the previous three decades, which in turn was balmier than all the decades before that back to 1901. Seems like something’s going on here, eh? I wonder what?

Take the Great Falls, Montana, area, where the average temperature for the month of December was 37.6 degrees Fahrenheit, nearly 12 degrees above normal. On one day, the high reached a whopping 64 F (a daily record) and the low dropped only to a balmy 51 F, for a daily average that was almost 30 degrees above normal. Meanwhile, the region received just .08 inches of precipitation for the month. Some more stats to ponder:

31: Number of monthly high maximum temperature records tied or broken across the West in Dec. 2023.

100: Number of monthly high minimum temperature records tied or broken across the West in Dec. 2023, including a 57 degree overnight low in Troutdale, Oregon, on Dec. 5 and 46 degrees in Benchmark, Montana, a whopping 5 degrees higher than the previous record low set in 2020.

0: Number of lowest minimum temperature records set across the West during December.

Wyoming seems to be bearing the brunt of the aridification this year. Statewide, the snowpack is now lower than ever recorded for the first of January. Ack.

And check out these stats from the National Weather Service’s Riverton, Wyoming, office:

Colorado is generally dry, as well, especially in the southwestern corner.

And Oregon? Blargh.

The only kind of bright spot seems to be in the Gila River Basin in southern New Mexico, where a good storm brought things up to the median for the period of record:

Here’s hoping El Niño kicks in soon.

⛏️Mining Monitor ⛏️

Energy Fuels, the operator of the White Mesa uranium mill in southeastern Utah, says it is ramping up long-idled mines in response to high uranium prices and “supportive government policies.”

In 2024, the company says it will recommence production at:

The highly controversial Pinyon Plain Mine near the Grand Canyon.

The La Sal and Pandora Mines in southeastern Utah at the southern foot of the La Sal Mountains.

When those mines are fully up and running this summer, the company “expects to be producing uranium at a run-rate of 1.1 to 1.4 million pounds per year,” according to a press release, though the ore will be stockpiled, not processed, until 2025, “subject to market conditions, contract requirements and/or Mill schedule.”

If prices remain high (they recently topped $90 per pound), Energy Fuels may start producing at its Whirlwind Mine on the Colorado-Utah border west of the town of Gateway. And it also says it will begin permitting its Roca Honda mine in New Mexico, its Bullfrog complex south of the Henry Mountains in Utah, and two projects in Wyoming.

It’s wise to take all such news with a grain of salt. Uranium prices are quite high currently, but could crash for any number of reasons any time. And these mining companies are notorious for overhyping production numbers and opening timelines in order to lure investors. Still, it’s the first real sign that there may actually be a revival of sorts of the flagging domestic uranium production industry — and all that comes with it.

Most of these projects can be found on the Land Desk Mining Monitor Atlas.

It is frustrating, but not surprising, to hear this about the off-road vehicle lobby. Between 2005 and 2010 I participated in a quarterly discussion group between New Mexico environmentalist and off-road vehicle users that was intended to find some common ground and develop some general working standards we could agree on for off-road vehicles on public lands.

I found it to be an absolutely frustrating process, and it had me ripping my hair out. Here were a group of conservationist willing to compromise, and we were basically met with the run around and a bunch of head games. At the end of the day, off-road vehicle users, were not willing to compromise. In fact, numerous times, participants flat out told me that they should have the right to go wherever they want and do whatever they want with their off-road vehicles. Any sort of restrictions at all, impinged on their freedom they claimed.

Which goes to show, these are just the type of people that need to be heavily regulated. Since they are unwilling to compromise and work for the common good, they need to be regulated.

Now, while there are certain off road vehicle users that are more reasonable, I find that by far the majority of off-road vehicle users, and the off-road vehicle culture in general is extraordinarily self-righteous, selfish and uncompromising.

I too continue to be puzzled by what appears to be total intransigence on the part of the off-road promotion organizations. The current Labyrinth Canyon issue is a good example, 100 miles closed, 800+ miles open to ORV's. In a nutshell, road density is directly related to the number of species that can survive in an area. More roads, fewer species. So the demand that there be no limits whatsoever on ORV use reflects the view that the species just don't count in any significant way. The only thing that counts is a users "personal pleasure and enjoyment". This level of self interest would is expected in a 2-year old, but means catastrophe for the natural world. Maybe I'm naive, but I think its likely that the ORV promotional groups don't fairly represent the mass of ORV users who understand the need for reasonable rules, any more that the NRA represents the views of every gun owner in the nation.