Storms help snowpack, but it remains scant -- and deadly

Plus a reupped interview with a snow nerd from 2021

The good news: A series of storms slammed the Sierra Nevada in California and large swaths of the Interior West, leaving a lot of snow, snarled roads, and a significantly improved snowpack.

The bad news: The new snow piled on top of the thin layer of old, weak snow led to avalanches, including one near Donner Pass in California that took nine lives, another in Utah that killed a snowmobiler, and yet another one near Brighton Ski Resort in Utah that killed a 13-year-old skier.

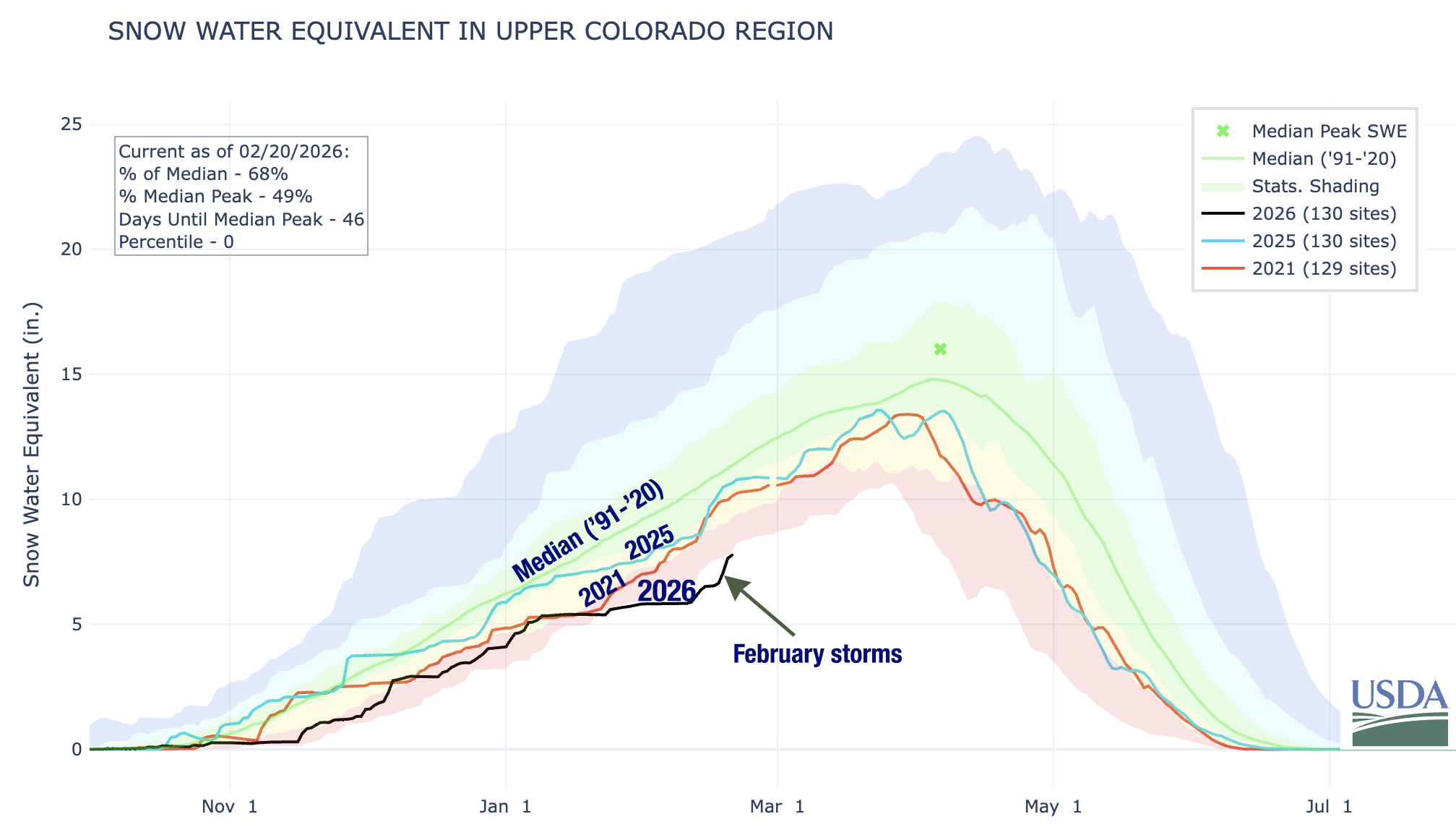

The storms have not been enough to boost snowpack to anywhere near “normal” levels, nor have they significantly altered the rather grim spring runoff forecasts. Indeed, the aggregate snowpack at 130 SNOTEL sites in the Upper Colorado River Basin remains at a record low. More storms are on the way.

And, to illustrate how wacky the weather is these days: Even as a big winter storm barreled through the region, massive wind-driven wildfires scorched thousands of acres on the Great Plains in eastern Colorado, Kansas, Texas, and Oklahoma.

You may be wondering why there are so many deadly avalanches when the snowpack is so thin. To help with an answer, I’ve re-upped this post from 2021, when the snowpack was at record lows in many places, and avalanche fatalities were at near-record highs. I considered leaving out the “data to consider” prologue part, since it’s five years out of date, but then realized it adds interesting context — and much of it applies again this year.

Scant-but-deadly snowpack

From the Land Desk, March 3, 2021

Some data to consider:

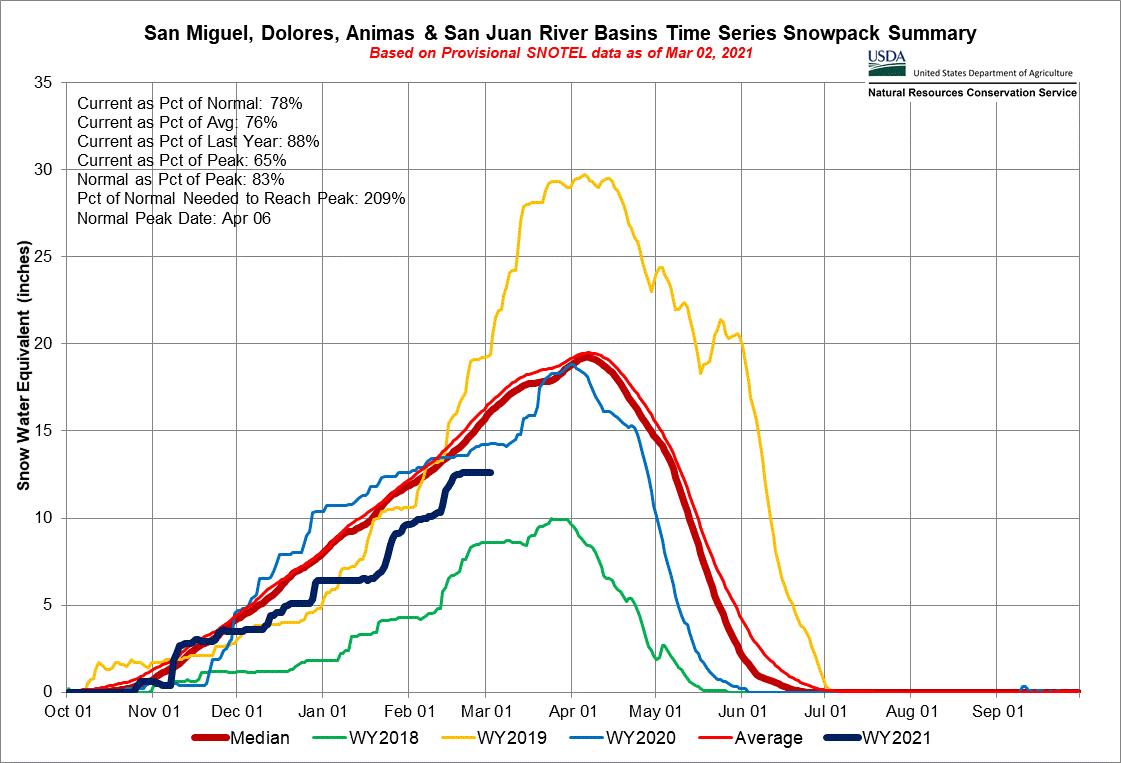

the Animas River in southwestern Colorado, an indicator of San Juan Mountain snowpack, hit a record low in December and then again in February;

the San Juan Mountains are in the grip of severe to extreme drought;

snowpack levels in the region are well below average; and,

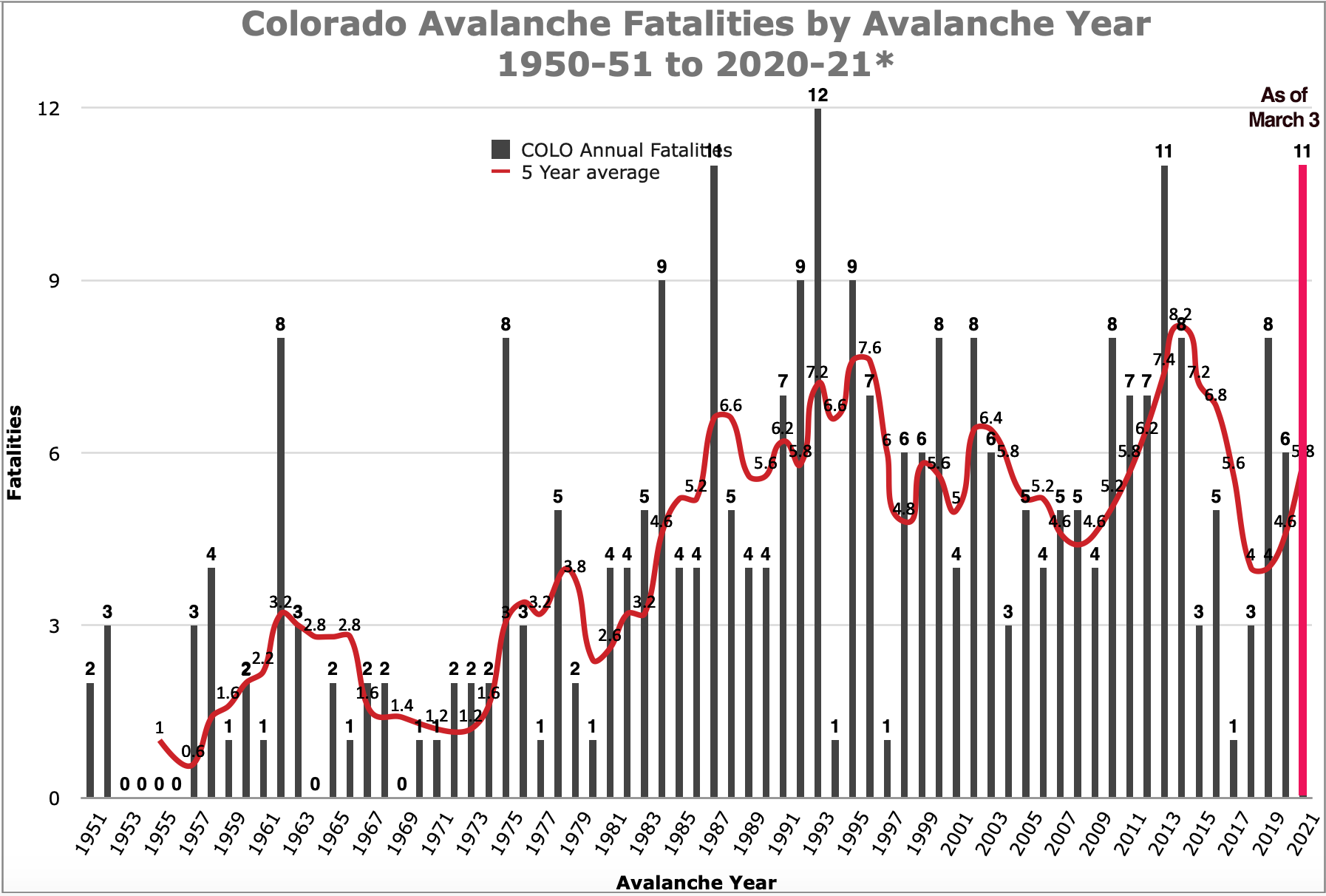

this winter is on track to break Colorado’s 70-year avalanche-related fatality record.

It may seem like the last point doesn’t fit, that perhaps the Land Desk got this year’s figures mixed up with those of the winter of 2018-19, when massive avalanches spilled down the slopes and shut down Red Mountain Pass for nearly three weeks. Nope. Thirty three people have been killed by avalanches nationwide thus far this winter and 11 in Colorado.

Surely this is partly due to more folks venturing into the backcountry, perhaps to avoid contagious ski-area crowds. But it is also due to an especially fragile snowpack: When layers of the snow are weak, they don’t bond as well, and the likelihood of catastrophic failure increases. And a thin snowpack can be even weaker than a fat one—and every bit as deadly.

I wrote about this for High Country News and my partner in dataviz-crime, Luna Anna Archey, put together some nifty infographics to help explain it. Please take a gander.

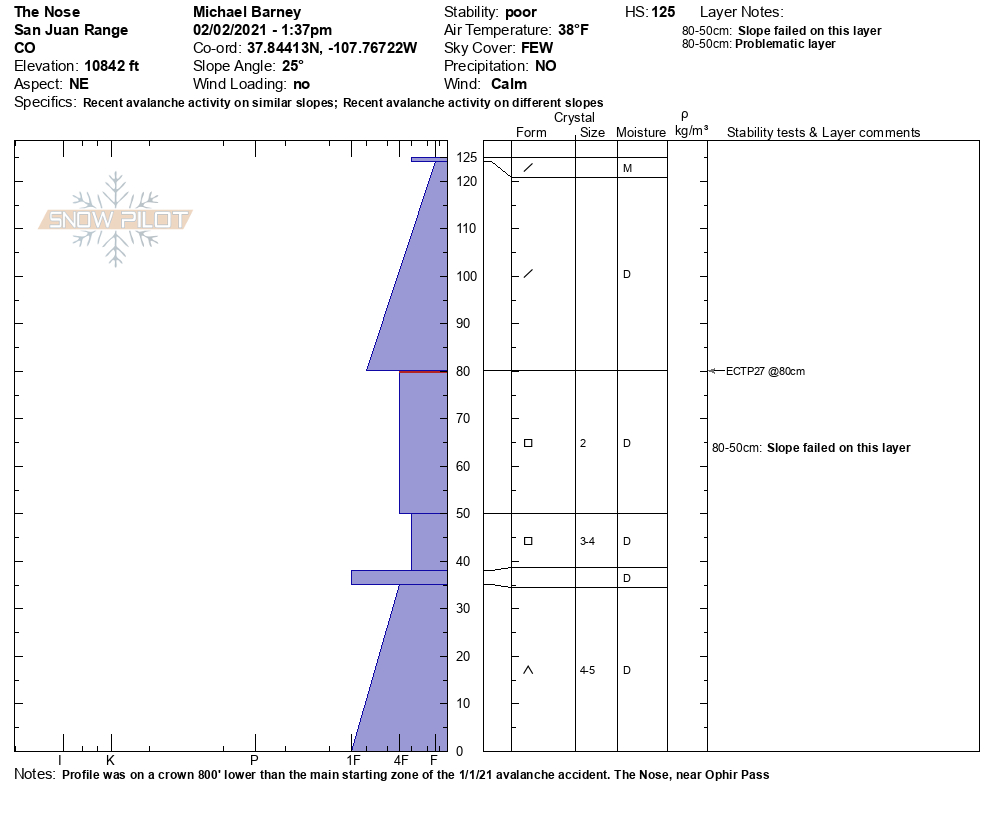

I’ll admit that when I first dove in, the whole notion of less snow leading to more snow-slide deaths struck me as counterintuitive. So I asked snow-nerd* extraordinaire, Andy Gleason, to explain the mechanics of it all to me. I was particularly interested in the setup for the tragic accident that occurred in early February on The Nose near Ophir Pass, when four people were buried, three of whom died. The following is a rearranged version of an email conversation I had with Gleason (I didn’t change any of his responses, only changed the order and lightly edited the responses so that they would be easier to follow; bolds/italics mine):

LAND DESK: Would you agree that this year’s conditions are especially dangerous, and that is a reason for the high number of deaths so far?

GLEASON: Yes. The reason is the weak, faceted crystals at the bottom of the snowpack. Often called depth hoar, these faceted crystals form when snow is subjected to cold temperatures while the snowpack is relatively thin. This occurs when we get early season snowfall and then a long period of clear and cold weather, like we did this fall in SW Colorado. Incidentally Utah [where four people were killed in a single accident in early February] had the lowest snowpack in recorded history in the first part of January, so they had a large depth hoar layer.

LAND DESK: How does depth hoar (known to the Germans as Schwimmschnee, or “swimming snow”) form?

GLEASON: Snow metamorphism occurs when a temperature gradient (difference in temperature) drives vapor through the snowpack between grains to form flat faceted surfaces that are not well bonded. Vapor moves from high pressure to low pressure, but it is impossible to measure vapor pressure gradient in the field, so we use temperature gradient as a proxy because warm air holds more moisture than cold air. The vapor sublimates from the ice crystal and moves up through the snowpack because the temperature at the bottom of the snowpack is close to 0 degrees Celsius and it is generally colder at the top of the snowpack. When the snowpack is shallow, the temperature gradient is larger and moves more vapor through the snowpack, creating more facets and a weaker layer.

This is the key: poorly bonded facets at the bottom of the snowpack form a weak layer that collapses easily and causes failure, propagating avalanches across large distances. When this weak layer gets buried by new snow, it is easy to trigger an avalanche because the lattice structure of the depth hoar is so weak compared to well bonded snow.

LAND DESK: Can you unpack the snow profile done by the CAIC after the accident at The Nose?

GLEASON: The scale at the bottom is a measure of snow hardness or bonding between grains. [The wider the purple part, the harder the snow. “I” (Ice) is hardest; “F” is soft enough that one could push into it with a closed fist]. When you have a difference in hardness between layers, especially when there is a harder layer above a less hard layer, it is easier to trigger an avalanche on that interface, as the bonding between the layers will be poor. The other thing to observe about the profile is the grain type, or crystal form. The square symbol is a facet and the upward arrow is depth hoar. The avalanche failed on the layer between 80 cm and 50 cm on 2mm facets. After it released, it stepped down into the depth hoar at the bottom and entrained more snow. This is dangerous because the more snow that is entrained, the more snow there is available to move downslope and bury a person. So if there is depth hoar at the bottom of the snowpack and it gets buried, it may not be the layer that is triggered by a person, but the weight of the avalanche will step down into the depth hoar and make for a larger avalanche.