"Shaping an urban area" in the rural West: Part I

A 50-year old Durango planning document and your chance to play the "used-to-be" game

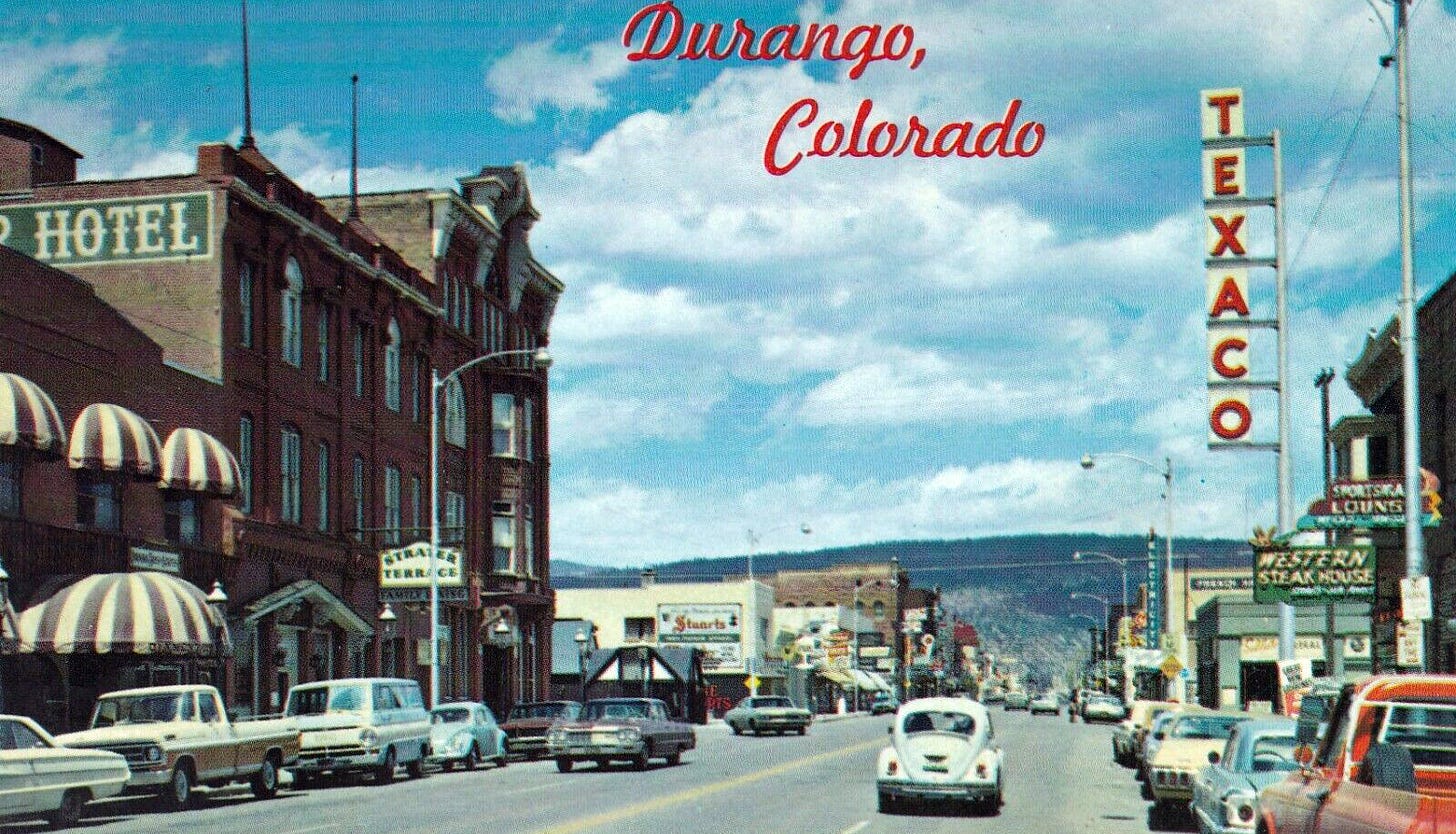

The manila envelope arrived in the mail last summer, containing a long-tabloid-sized document on aged, brittle newsprint. The washed out cover photo was black and white, but it was framed by a thick blue square. Sunday, August 15, 1971, it said on the top right hand corner, then: DURANGO! Shaping An Urban Area above the old school Durango Herald flag.