Scrappy watchdogs gear up for a new mining boom with court victories

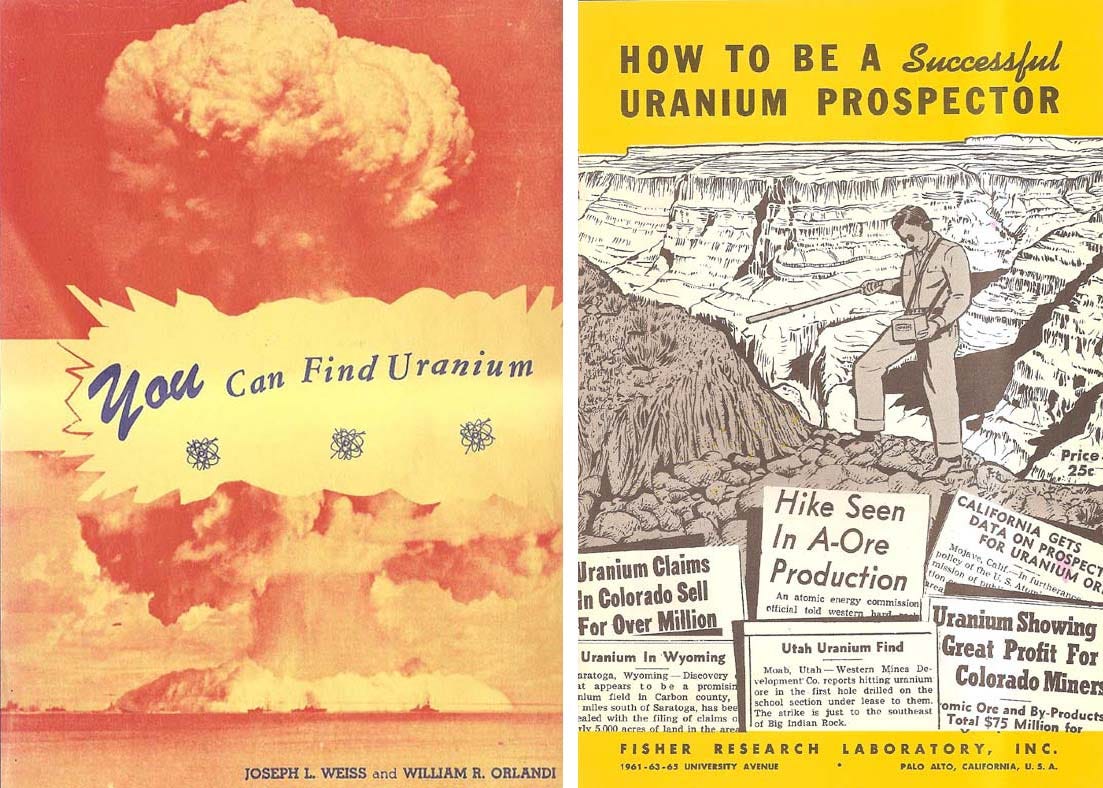

Demand for green metals and possible sanctions on Russian uranium could jumpstart the industry across the West

Here’s what’s great about electric vehicles: You don’t need to fill them up with dirty, stinky, volatile gasoline; they don’t spew any exhaust; and they contribute less to climate change, so long as they are charged on a grid not dominated by fossil fuels. Here’s what sucks about them: They are basically big, rolling batteries, and batteries need minera…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Land Desk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.