Meditations on Monkeywrenching

Also: The Data Center boom and the Four Corners Power Plant

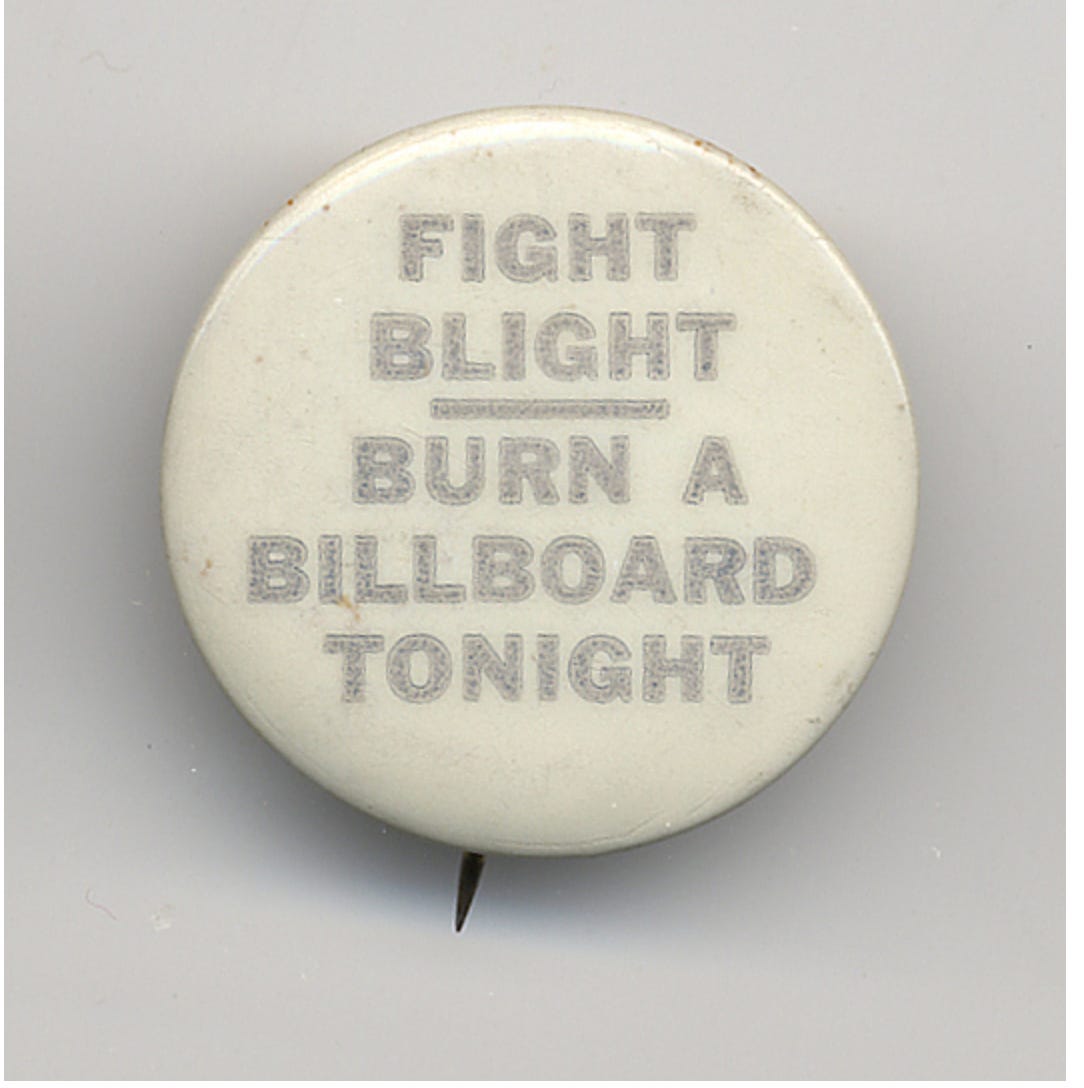

When I was a kid, I collected pinback buttons, political and otherwise. Most of you probably know what that is, but for the youngs out there, it’s basically an analog meme you pin to your clothing to let folks know which political candidate or other cause you might support.

I’m pretty sure I had a “John Anderson for President” button. My parents supporte…