Longread: On wolves, wildness, and hope in trying times

How Ol Big Foot's story restored a shard of optimism

🦫 Wildlife Watch 🦅

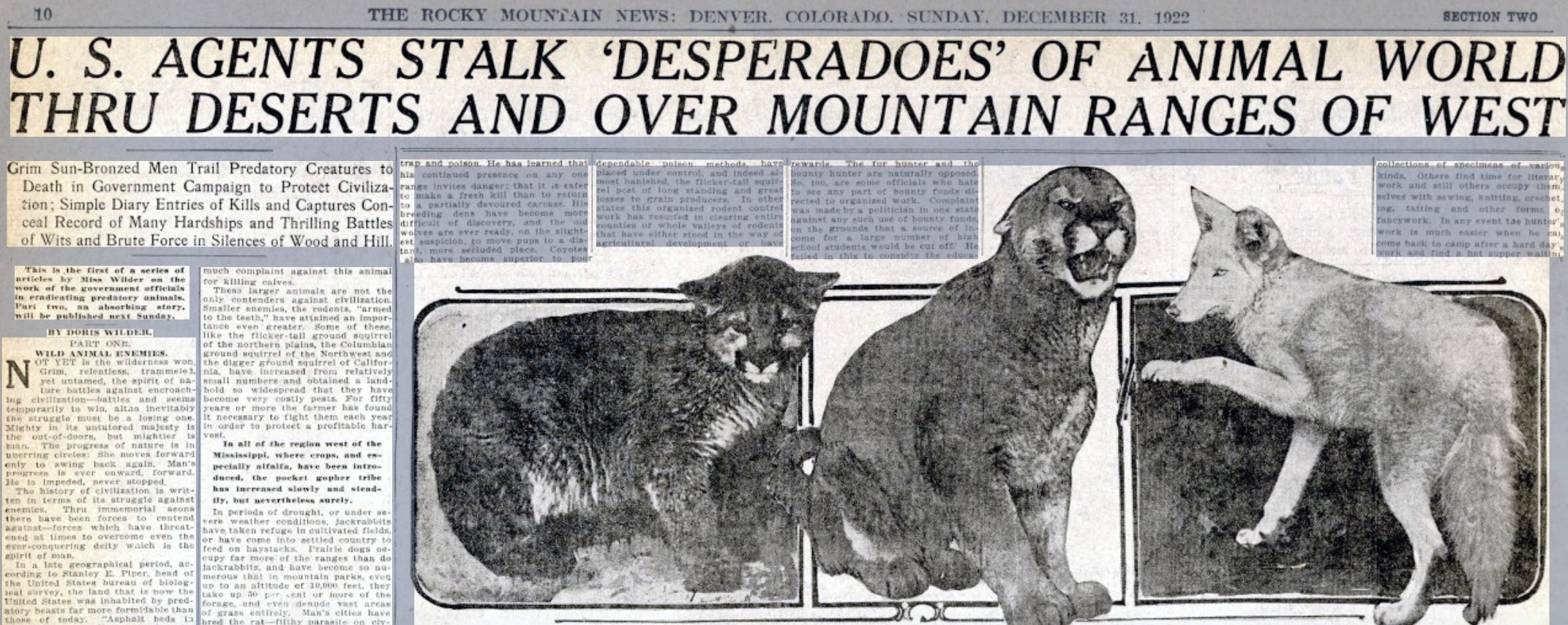

During the 1910s, a large gray wolf — christened Ol’ Big Foot by his human admirers and adversaries — roamed from one end of what is now Bears Ears National Monument to the other, from the sinuous White Canyon to Clay Hills, from the ponderosa-studded glades of Elk Ridge to the gorge-etched Slickhorn Country to the Colorado River whe…