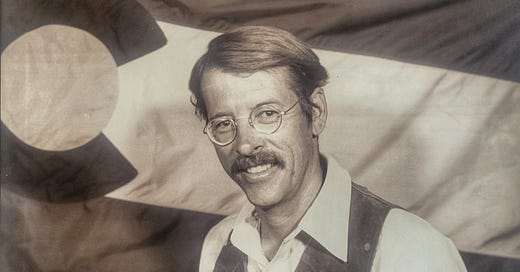

The San Juan Mountains lost a powerful advocate and influential character on Jan. 5 with the passing of William “Bill” Simon of Durango and Silverton, Colorado.

I first met Simon in 1996, shortly after I moved to Silverton to work for the Silvert…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Land Desk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.